A mother in the Western world might learn she is expecting with the confirmation from a simple, in-home test. She begins a series visits to her OBGYN clinic. There she will receive regular exams and ultrasound scans that track her baby’s growth and development, as well as monitor her own health. Using this information, her doctor has estimated the baby’s due date. In the days approaching delivery, mom and doctor have been in continual communication to track progress. On Monday night, mom goes into labor. She labors for several hours at home, perhaps knowing when her contractions signal she should move to the hospital. She will likely be driven in a private, family vehicle for the trip. She is pre-registered at the hospital and has identified how payment will be made—an arrangement which likely involved a health insurance provider. Upon arrival at her hospital, mom is immediately taken into her own private labor and delivery room. She will spend the next 1-3 days here, with only family members or close friends admitted at visiting hours. After her natural birth delivery, this is a quiet, special space for mom to bond with her new baby. On Thursday afternoon, hospital discharge occurs with ease. Mom trusts her baby is healthy and ready to go home, and the hospital trusts that finances will ultimately be taken care of.

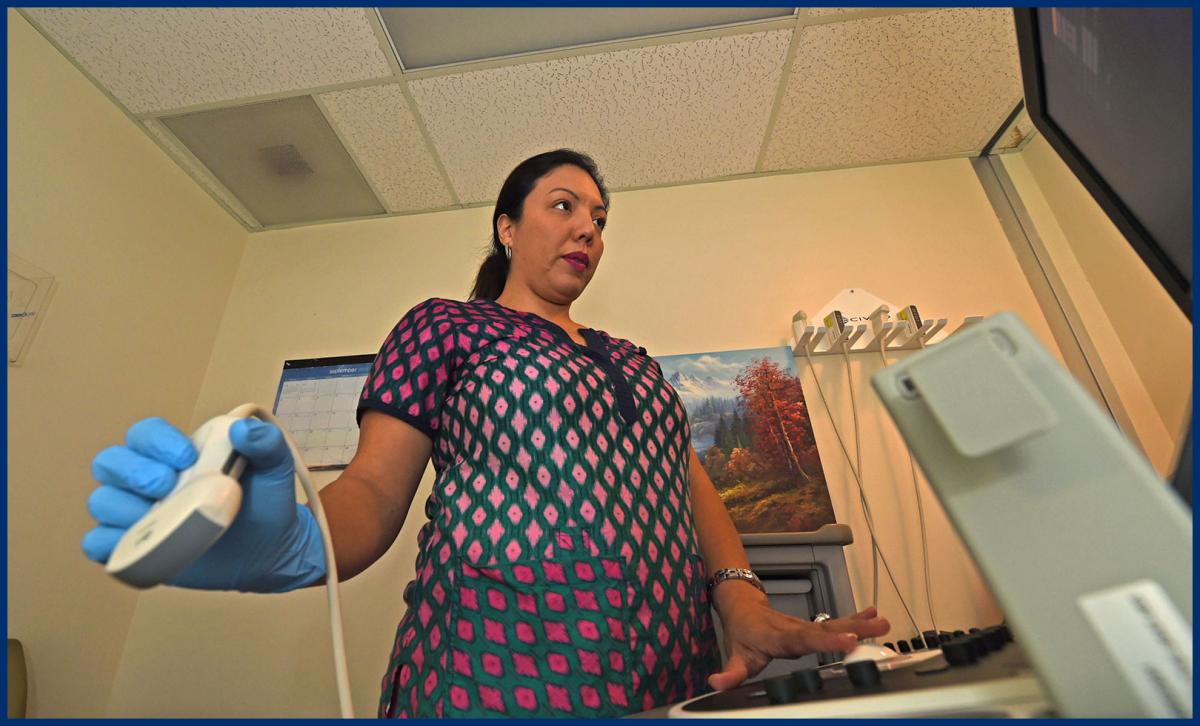

Left: An ultrasound technician prepares to scan a mother in the Western world. Right: Pregnant mothers wait for their babies to come in a ‘maternity waiting home’ in Zimbabwe. Photo: Ray Mwareya, 2017

Banner Photo: A mother is visited by doctors in the maternity ward of Kibuye Hope hospital, Burundi. Photo: J. Keiter, 2019.

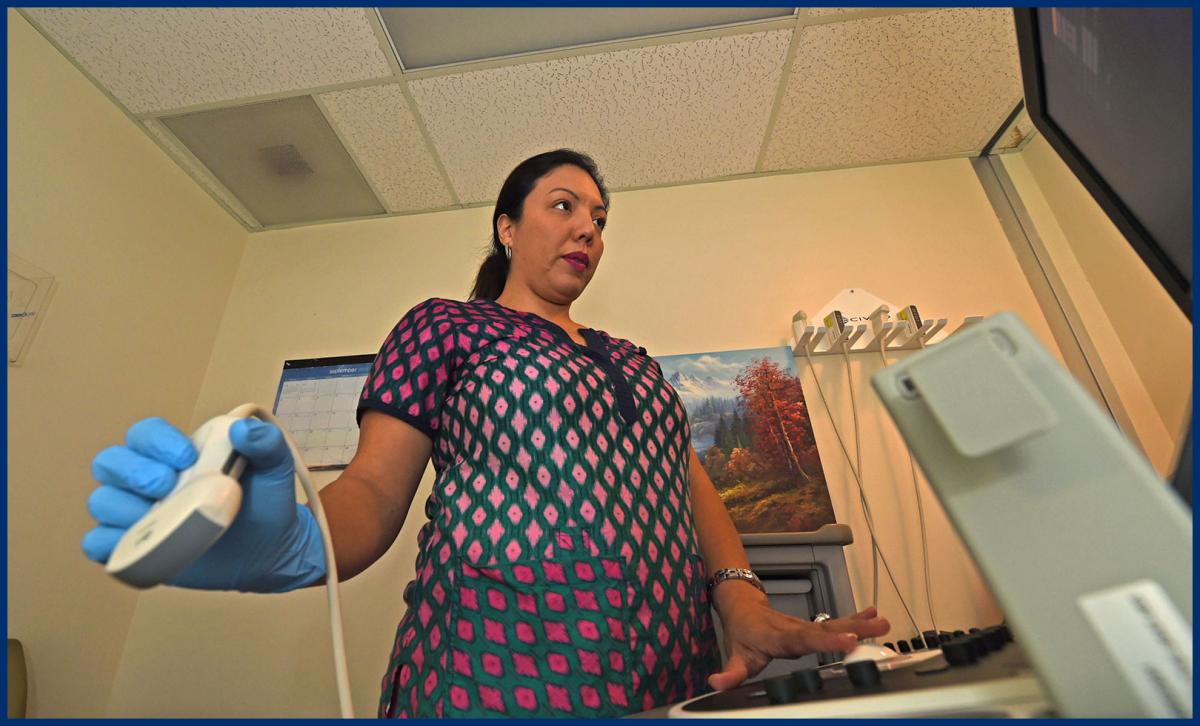

By contrast, a mother in the Majority world might realize she is pregnant only after the first trimester. She may lack access to early verification tests and likely does not have regular access to an OBGYN. Instead, she may visit a clinical nurse who can assist in verifying her pregnancy and evaluate her progress. The birth might fall during harvest season or otherwise affect her efforts and commitments to both her family’s and her own economic welfare. The family determines how and where mom will give birth. Let’s presume she will give birth at a healthcare facility and not at home. Facilities equipped to handle the medical sophistication of a birth may be few and far between—both in distance and availability. Mom could be facing a four- to eight-hour trip, or even a multiple-day journey using rudimentary transportation. Without confidence of when her baby is due, mom wisely chooses to travel on a conservative schedule. She may arrive at hospital a month prior to delivery. If so, she will make herself at home in a “Waiting Village”, where she and other expecting moms simply bide their time and wait for their babies to arrive.

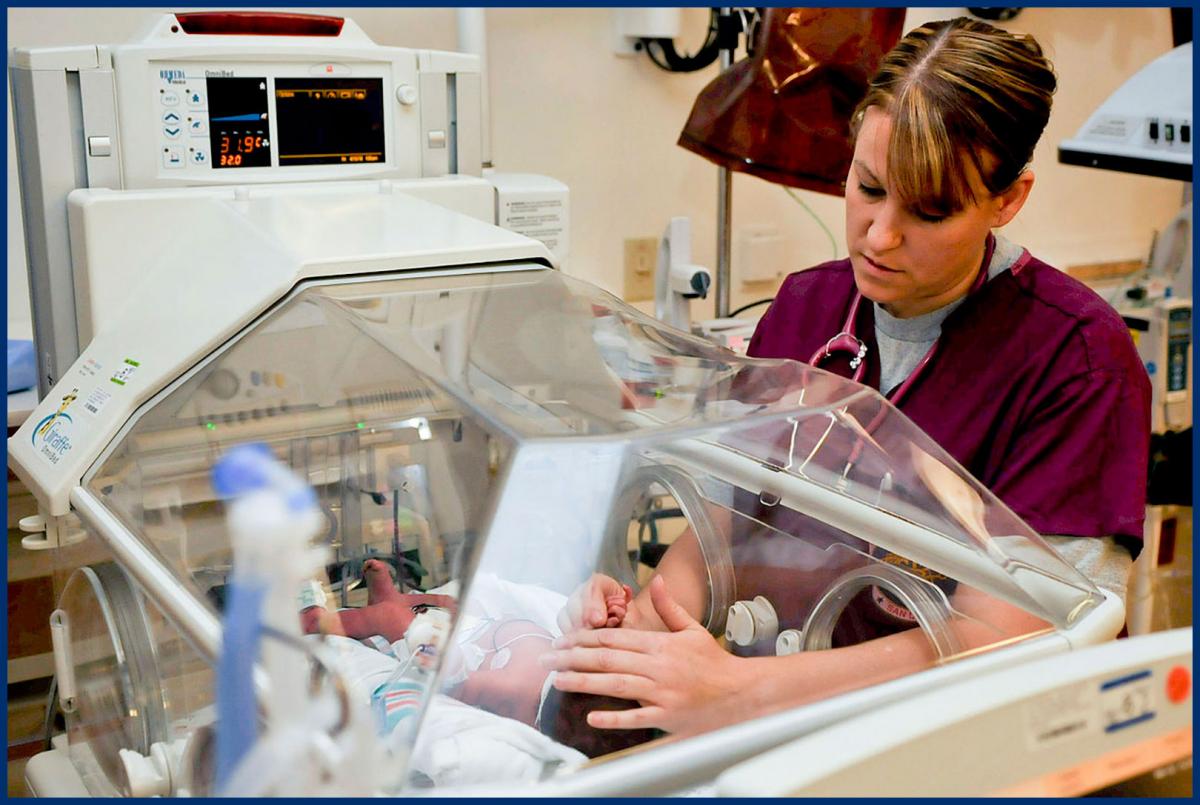

When labor begins, she moves into the labor ward. She and perhaps 10 other women labor and deliver in a large open room with family aides and hospital staff in attendance. Curtains cordon off beds to provide some separation and privacy. After welcoming her new baby, mom and baby will move to a similar open ward for recovery. Sometimes there is a NICU or post-delivery area for infants. But more often than not, babies stay with mom whether or not they have any issue requiring medical intervention. Payment of the hospital bill at discharge often presents difficulties. Though mom may be receiving heavily-discounted healthcare services, there is still a payment expectation that could be challenging for her family. She is not equipped to pay the bill and family aides will start working to gather funds. She might need to linger in hospital as a “Discharge In-Patient”. These are patients who are medically fit for discharge, but whose payment arrangements have not been finalized yet. Mom and baby may stay here 2-5 weeks before the journey back home to an expectant community of open arms.

While these stories are certainly generalized, they offer a glimpse into the polarized reality between healthcare in the Western context and that commonly encountered by EMI project teams in the Majority world. With these stories in mind, let’s explore a few ‘poles’ of distinction between the two contexts as they relate to healthcare architecture.

Left: A private labor and delivery room at a Western hospital. Photo: Scott & White Healthcare CC BY-SA 2.0. Right: In-patient ward at Kibuye Hope Hospital, Burundi. Photo: J. Keiter, 2019.

Patient choice v. Patient focus

In North American health systems, patients have choices in varying degrees. Choice to go to hospital A or hospital B—each likely within 10 miles of the other. Choice for doctor A or doctor B or C, etc. As a result, healthcare providers face challenges in a competitive market to securing patients. Facilities have evolved from historical institutions to virtual health clubs. At the same time, patient choice is tempered by insurance, fiscal, or system constraints.

In Majority world healthcare, patient choices are far different. One fundamental choice is between government facilities and non-government providers. The former are typically overwhelmed and understaffed, and many have poor reputations for care. The latter may be private, commercial facilities or religious institutions. In rural settings, many are Christ-centered ministries. Resources and attention at Christian hospitals are intentionally directed toward patients and their guardian families. They commonly have a goal of ‘holistic care’ which means a commitment to quality curative care in tandem with compassionate evangelism.

Patient turnover v. Patient connection

Given Western health service is expensive for a multitude of factors, facilities and patient care are driven by efficiencies. Whether economical, spatial, staffing efficiencies or the like, rapid patient turnover, or throughput, is the target. As with the previous maternity example, "You can stay three days, but only one or two are preferred.” The hospital needs the room back; it needs the financial gains of turnover. Despite the emphasis on personal patient care, patient throughput and subsequent billing dictate procedures.

In mission hospitals, however, there can often be great intentionality toward patient connection. As in the second maternity example, if mother and child should prolong their stay an additional week or two, the hospital staff view this as an opportunity to deepen a spiritual connection with the family or educate and equip them for better long-term health.

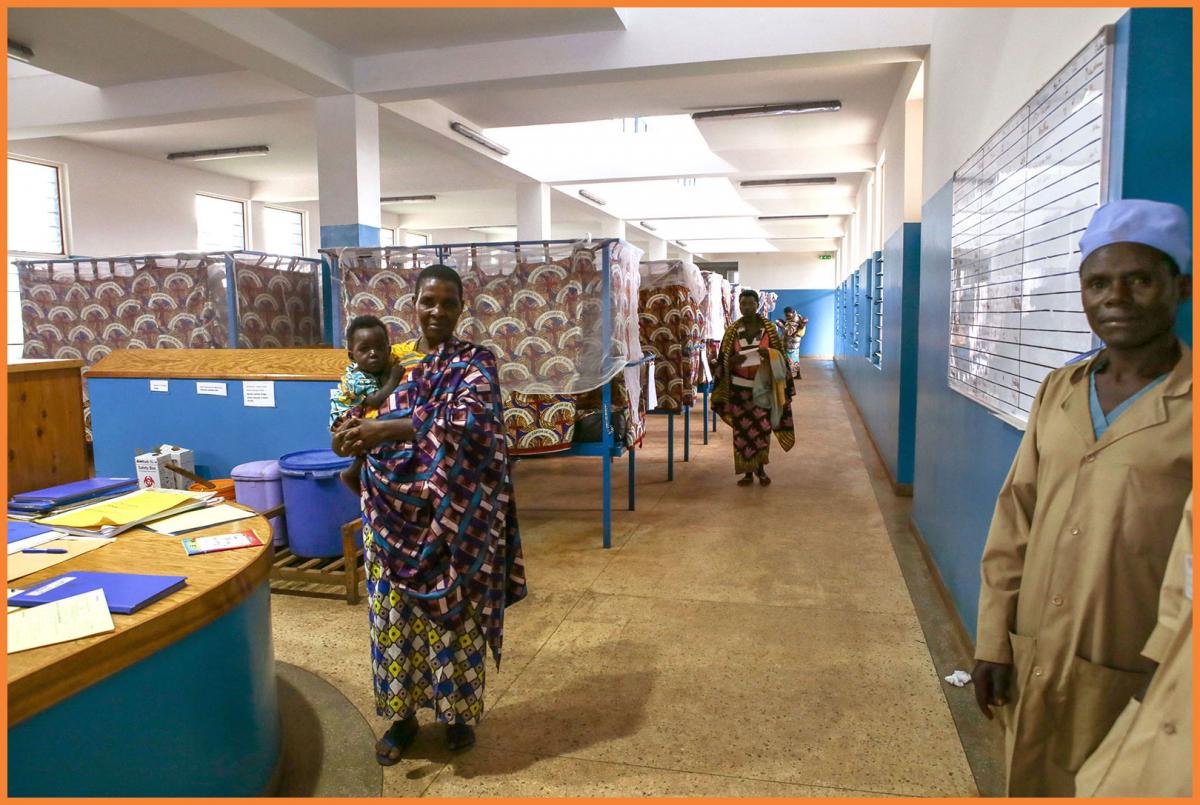

Left: At the NICU in a Western hospital. Right: At the NICU in Kibuye Hope hospital, Burundi. Photo: J. Keiter, 2019.

Diagnostic technology v. Limited resources

Western healthcare remains at the forefront of technology. Cutting-edge and often hyper-expensive technologies for diagnostics, robotic surgery, and radiological equipment are expected within market choice and elevate the quality of care.

In Majority world settings, limitations of resources limits the level and form of technology in healthcare. Christian hospital providers often face limitations such as unreliable power availability, inconsistent maintenance, or incompatible donated equipment. These may be coupled with under-trained or insufficient staff or medical resource supply challenges.

Codes v. Best practice

In the Western context, architectural design is predominantly determined through codes. These include: International Building Code (IBC), life safety (NFPA), and in the case of healthcare design, FGI guidelines. These codes present minimum standards or basis of design, and largely determined by health, safety, and public welfare boundaries. They are also the enforcement reference from initial permit review to the extreme of litigious accountability.

In the Majority world, code guidance, compliance, enforcement, and accountability is not the central element of healthcare architecture. EMI project teams are often requested to design to “international health standards” for two purposes: Local codes prescribed by ministries of health may not be available or developed to sufficient detail. Weak code enforcement or corrupt code enforcement create situations where standards are either avoidable or not apparent, or perhaps complied to in name only. However, our healthcare clients see a moral obligation (akin to the Hippocratic Oath) to uphold reasonable standards of practice in physical plant design and as agents of care.

These “best practice” standards are often pragmatic in nature and learned over the course of time or by experimentation. They are not necessarily determined with reference to code compliance. For example: “We have been utilizing this particular triage and admittance process for 20 years and have noticed that certain patients need to flow this specific way…", or, "our sterilization process for surgery happens best in this manner due to this system we have put in place…” Whatever the scenario, EMI designers are looking for a solution positioned somewhere between Western code requirements and expectations, and local “best practices” which may no longer relate to any official health standard.

Left: The elevator bank at a Western hospital. Photo: UMHealth System, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Right: Accessibility ramp at Faith Mediplex Hospital, Nigeria. Photo: B. Banta, 2016

Building technology v. Passive systems

Western healthcare architecture design presumes that active building infrastructure technologies are available, reliable, and fully integrated throughout the campus. With technology, we find conditioning of power, comprehensive security, pressurized mechanical systems, mechanized access between floor levels, to name a few. Add to each multiple layers of backup redundancy.

By contrast, passive design elements are most readily used in the Majority world where infrastructure and resource access or availability is constrained. Multiple single-story buildings with passive cross ventilation are more common than a single, large multi-level structure reliant on conditioned air movement. Long external ramps are the only reliable means of floor access when elevator banks are untenable or unreliable.

Each EMI hospital project location has its own unique expression of healthcare practices and culture values which are at variance with the Western healthcare industry. The opportunity for EMI healthcare architecture is to find the appropriate balance point between such polarities. This kind of healthcare design is developed through awareness, sensitivity, and creative responses.