Making our designs usable for all

The United Nations estimates that over 75% of all individuals with disabilities live in the majority world. Additionally,

An estimated 20 percent of the world’s poorest persons are those with disabilities; 98 percent of children with disabilities in developing countries do not attend school … and the literacy rate for adults with disabilities is as low as 3 percent.Note 1

Because EMI serves primarily in majority world countries, this means that 20% of the population that EMI serves have disabilities of one kind or another. But we don’t always see them, because they can be hidden from public view. This is not uncommon in many of the cultures where EMI serves. This should be one of the drivers of why we do what we do. And it also suggests that some of the more common buildings that EMI designs, like schools, housing, ministry centers and medical facilities, should be designed with those having disabilities in mind.

Now let’s talk about simple steps as to how we as EMI can be part of the solution. Since disability is so interconnected with poverty, significantly diminishing world poverty is less likely unless the rights and needs of people with disabilities are taken into account. Many people would consider this to be part of the poverty trap,

Poor people with disabilities are caught in a vicious cycle of poverty and disability, each being both a cause and consequence of the other.Note 2

What does this mean? Let us do our part to design accessible sites and accessible buildings, especially if there is little additional cost to the project. By using design, EMI can reduce the physical barriers hindering people with disabilities from being full participants in society. Here are four practical steps to consider:

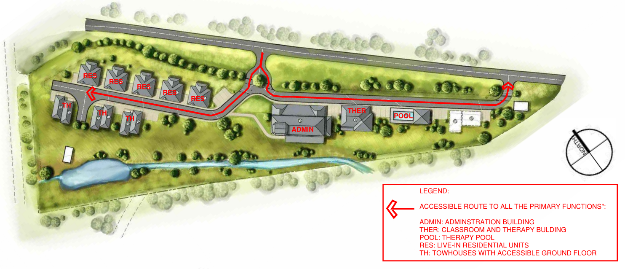

- When locating a building on site, locate the ones with the primary functions along an accessible route.

- If possible, design one story buildings rather than multi-story buildings.

- Provide basic guidelines/details and dimensional constraints for each element on the accessible route.

- Keep it simple and use common sense.

Below are two case studies to highlight the above 4 points.

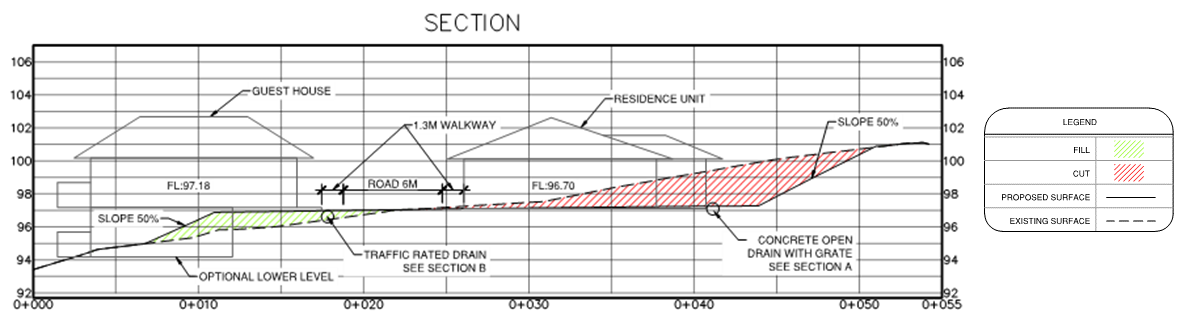

The QUAD-E project is a live-in community for people with special needs. In lieu of the client-requested multi-story admin building, EMI proposed utilizing primarily one-story buildings for all the required program functions. We did this for two primary reasons:

- Elevators for a multi-story building are a good way to gain accessibility in wealthier countries, but can be expensive in remote areas or countries where availability and maintenance of elevators is challenging.

- All the required program can be accessed from the ground floor; whether it be pedestrian or vehicular access to the front door. Redundant and secondary program functions where a person with special needs does not require access can be located above the ground floor. In the world of accessible design, this is known as providing access to the “primary functions” to everyone regardless if they have a disability or not. Secondly, this also exhibits another accessibility concept known as “visit-ability” which is the ability of everyone to visit each other in the spaces where each one of us work, live and play – regardless if we have a disability or not.

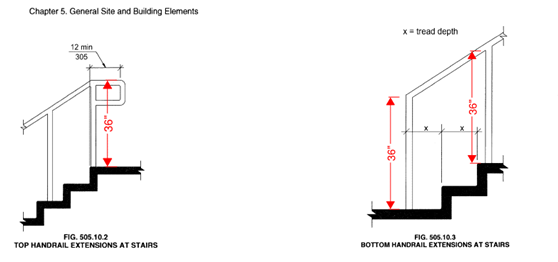

Another case study is Haiti Arise, which is a campus that EMI Canada has visited 4 times in the past 10 years. In addition to designing a new birthing clinic, church expansion and some re-planning, one of the tasks during our 2018 visit was to evaluate buildings already built. Below is an example of a built handrail for a school building reviewed during this visit. As you can see, the height of the handrail gets shorter and shorter as you ascend the steps; not good for someone who has even a slight disability.

After reviewing the existing stair railings, we would recommend the dimension to the top of railings be 3’-0” above the stairs to match dimensions of most model building codes. The green dotted line represents something closer to what a code compliant railing is if we used typical model North American codes.

In addition to the one-sentence recommendation, a couple of simple diagrams from the model code were added for reference. No need to quote entire code books, as designers try to pick and choose the most important details to share to a Client ministry:

Fortunately, when the birthing clinic was built in 2019, the railings were indeed built much more consistent to the dimensions and details provided. Sometimes, these simple guidelines and details are all that is needed to promote accessible design in a majority world context where such codes and diagrams are not readily available.

A word of caution however about codes. Although it is mostly true that modern day codes are the most robust for accessibility, it is not always the case. Let’s use these same railings as an example. ANSI A117.1Note 3 is the accessible design standard for most new buildings in the US since it is referenced by the International Building Code (IBC). Hand railing extensions from the 1992 version of ANSI A117.1 were shown to extend at the bottom of stairs for one tread plus 12 inches. Although this seemed like a good idea for those with disabilities, it proved to be slightly more hazardous for the general population in terms of egressing in a life safety situation. Architects and others in the US lobbied for a common-sense change so that handrails could be suitable to both the general population and those with disabilities. Fortunately, this was updated in 2003. Depending on when each state adopted ANSI A117.1, new buildings designed in the US during this approximate 11-year span between (1992 to 2003) had handrail extensions which, although were better for individuals with disabilities, were indeed slightly more challenging for the general population.

All this to say that as designers of buildings and structures in majority world countries, sometimes we just need to use common sense and use our experience to design something that balances accessible design with other needs.

Additionally, as part of our due diligence, we should research what codes are available in the country our design work is being used. At the very least, consult the local design professional on your EMI team in regards to local codes.

An excellent example of a local code that exceeds North American standards arose in the QUAD-E project, where the maximum slope for an accessible ramp is 1:14. This is more conservative than the 1:12 used in most model codes in North America.

Accessibility is for everyone. So why not try to document something culturally appropriate, accessible and constructible in the context in which we are designing? And even though we do not always see those with disabilities during our visits, we should always keep them in mind. Remember, 20% of the population that EMI designs for have physical disabilities.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.