Design lessons learned in EMI’s practice of Healthcare Architecture in the Majority world

Master planning for healthcare facilities integrates many complexities into a site mosaic. Beyond site constraints, environmental opportunities, and infrastructure demands, planning must consider local standards and regulations, patient care functions, and a comprehensive understanding of healthcare operations.

EMI projects often present the added challenge of transposing western or international standards and practices into highly variable contexts in Majority-world cultures. The previous article on Healthcare architecture described this polarized reality; we now move on to offer a few specific design lessons learned.

Lesson 1: Outdoor Space is Patient Space

In the Majority world, in-patient beds are often clustered in gender-segregated wards of 10-20 beds. Often these wards are one large room where patient personal space and privacy is very limited. This is in stark contrast to the private or semi-private rooms that are common in Western hospitals. As they are able, patients seek out spaces beyond the confined, interior ward area – both for personal space and for exposure to outdoor elements. Outdoor spaces often allow for cooler, fresher air away from the constriction of ward walls. Patients in Africa (for example) often have a culturally- or socially-established idea that the healing process is enhanced by being outside. Whether it is sunshine, air movement, breathing fresh, ‘non-infectious’ air, or engaging with nature, the outdoor environment is held to be conducive to healing. Western designers are similarly exploring “Biophilic Design”, as the integration of experiencing nature in the built environment. This non-medical intervention leads to more holistic healing, as has been detailed in a recently published book of the same title.

Outdoor spaces also provide areas where patient caregivers or family members can gather around the patient, interact with each other, and watch kids play. These assistants often serve as informal nursing staff for the patient, making interior spaces more densely occupied and trafficked as a result. In the Majority-world setting, independent departmental functions are often scattered on a site campus and interconnected through open, covered walkways. Walkways are constructed externally to reduce internal construction cost and can smoothly mitigate any differences between floor elevations of separate buildings. These walkways are broader in width to allow for circulation of staff and equipment, and are prime opportunities for patient resting and socializing spaces.

Varying types and sizes of outdoor spaces can be intentionally integrated into the architectural program. Whether in the form of balconies off wards, private rooms, waiting spaces, or spaces through circulation corridors, environmental connectivity is a priority. Patients must be provided with a means to get outside that is proximate to their space – moving either by self, or with assistance from a caregiver.

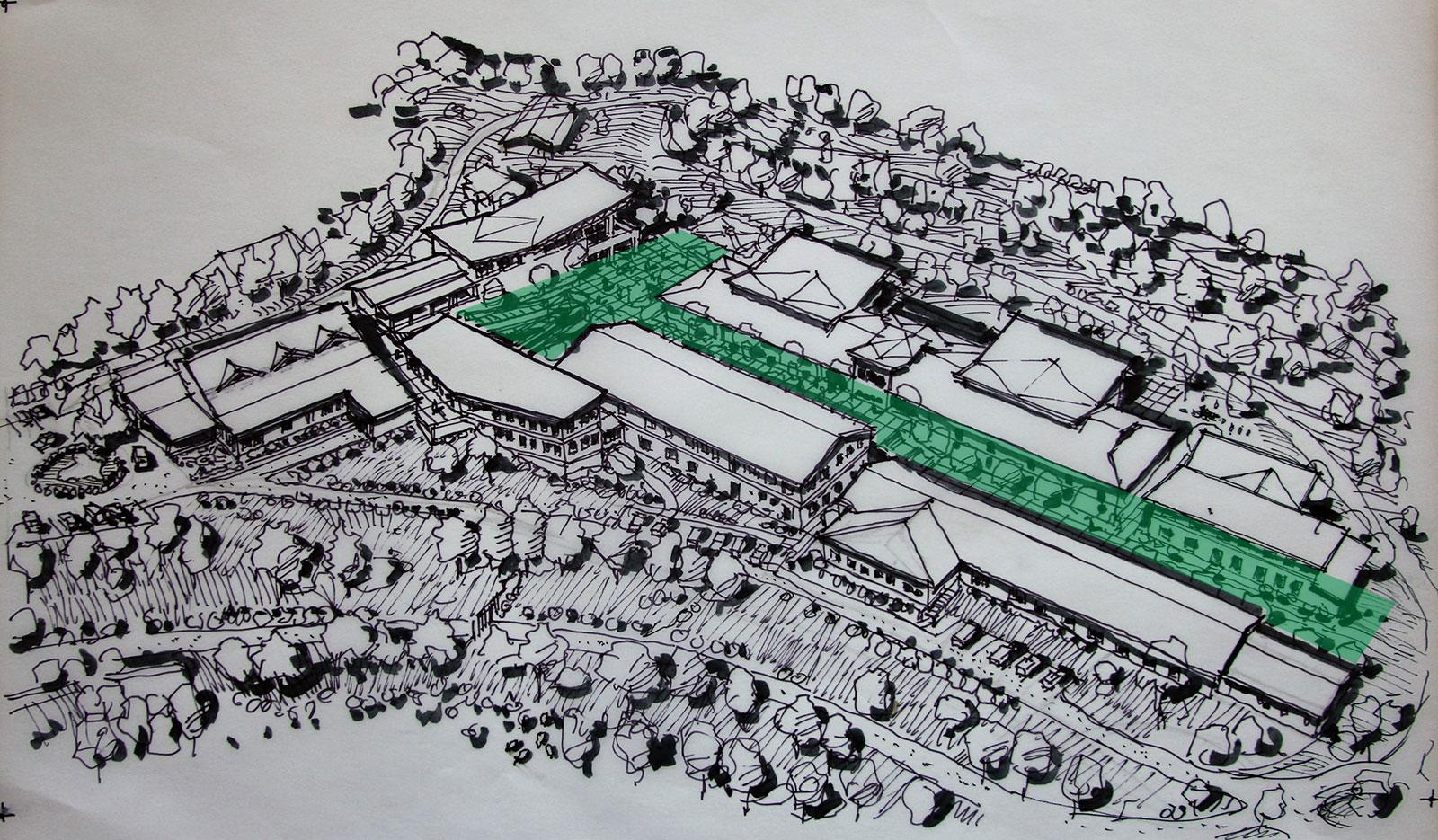

The design for Kapsowar Hospital in Kenya, a recent EMI project, purposefully includes two outdoor elements to address these objectives. First, there is a central courtyard circulation that facilitates movement of staff, family, and patients. This circulation path is located between the multiple buildings that comprise the outpatient clinic and inpatient wards. Circulation areas are deliberately generous in width, recognizing that patients will utilize those covered and uncovered sunny spaces for both waiting and recovery. This space is intended to have a balance of vegetated areas, covered areas, and pockets of sunshine – all opportunities to promote healing through experience of the outdoor environment.

Secondly, the inpatient spaces are positioned strategically to take advantage of sweeping panorama of the valley beyond. Internally, patient beds are oriented at 15° angles for variety of reasons, but this also promotes visual engagement with the natural beauty out the windows. External balconies are located off the wards to allow patients to be rolled out to sun themselves and enjoy the beautiful vistas. Typically, such a building would terminate at the end wall. However, it was considered imperative to extend toward the outdoor space to enhance a patient’s holistic experience in and through the mission hospital.

Lesson 2: Infection Control with Passive Ventilation

Healthcare facilities are often at the nexus for disease and control – not only for treatment, but for containment as well. Recent events with Ebola and the novel coronavirus have only solidified concerns in the public eye. Infection control is defined as “the non-transference of infections among patients or staff.” In North American hospitals, infection control between adjacent patients is often achieved through the separation of patients. This is one of the many reasons for private or semi-private rooms in contrast to the multi-bed ward arrangement. Secondly, infection control in Western facilities is managed by air control: through an active HVAC system (including intensive filtration), through controlling air movement by mechanically-created negative and positive pressures, and through isolation spaces as necessary. Through intense research and countless journals, consensus regarding optimal intervention remains ongoing, even with availability of highly-advanced mechanical technologies.

In the Majority world, active HVAC systems are often highly cost-intensive, simply not available for installation, or impractical to maintain. For these reasons, passive ventilation remains the only viable option for many healthcare facilities – both for optimal air changes as well as comfort control. However this limitation presents a challenging dilemma. This is simply because passive ventilation – even when a space is deliberately designed to promote active air movement – still relies on wind and pressure which are dependent on climate and season. Active air movement cannot be presumed on or regulated throughout the day or on any given day. Neither can adequate air filtration nor rapid air changes be realized with the passive ventilation model. Proactively encouraging passive, non-mechanical ventilation as an element to our designs is critical for comfort through unconditioned interior spaces, and yet clearly creates challenges in effectively controlling infection transmission through unregulated air movement. This predicament has prompted exploration toward alternative solutions to which both Western and local designers may be unaccustomed.

As mentioned previously, healthcare campuses in the Majority world often include multiple buildings spread out on a site rather than just one multi-level building for all care needs. This directly can have an impact on the practical integration of passive ventilation and infection control. One advantage can be as departments or functions are spread throughout, less critical mass of infirmed population are collected in one location. Greater separation of functions can allow for more air movement between functions, whether by virtue of open-sided covered walkways or simply through breezeway or buffer spaces between buildings. Beyond the opportunity for natural beauty, courtyards also offer air movement – allowing facilities to breathe as much as possible.

The Outpatient Department (OPD), however, is all too often the collection point for multiple clinics, infirmed, and non-acute. Thus, the OPD can contain concentrated areas of airborne disease. Say for example that a tuberculosis patient from a rural area arrives at the OPD. They do not know what day the TB clinic is on or where it is located. They enter the same space as all the other clinics, with mothers, children, and other healthy or unhealthy patients. Due to limited air movement in highly populated, passively ventilated spaces such as a waiting area, patients and family members could be exposed to infectious disease. An optimal solution is to divide waiting areas into smaller, designated, and detached spaces offering greater separation and air movement. For inpatient care in concentrated open wards, beds are often 3-4’ (1m) apart and independent private rooms are unavailable or unsustainable. However, by devising 4-8 beds in disconnected clusters with partitions between them, a degree of directed airborne containment can be offered even within an open ward architecture.

We’ve learned that environmental integration can positively impact healthcare design in the Majority world. Whether by capturing outdoor space for patients, seeking opportunities for visual connection to the outside, or through design promoting intentional air movement, quality and holistic patient-care can be given spaces to operate in – spaces which encourage healing in body, mind, and soul.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.