Merging traditional building techniques with modern reinforced concrete frames

EMI India staff get the privilege of traveling to almost every corner of this incredibly diverse country. But no matter the region or how remote it may be, the majority of new buildings are constructed in the same manner. With slight variations, the structural characteristics of these modern buildings include lightly reinforced concrete columns and beams, thin concrete slabs, and masonry infill. Around the globe, India included, people are abandoning traditional building materials and techniques in favor of concrete construction. Especially in rural areas, billboards for cement and reinforcing steel promote this growing trend of concrete use.

Building with concrete has several advantages in this rapidly urbanizing world: taller buildings can be built using relatively low-skill laborers, and materials are readily available. But there are also drawbacks: concrete and masonry infill which is cold in the winter and retains heat during the summer is often not suited to the regional climate. Ease of construction also means that these buildings are rarely engineered and are often of suspect quality. In seismic regions this makes them prone to collapse with dire consequences, as in Haiti in 2010, Nepal in 2015, and countless other examples.Note 1

A few years ago, an EMI India project explored a creative solution to combine both the advantages of concrete construction and the benefits of traditional building methods.

The India office of EMI has been assisting the Moravian Church in Leh since 2006. At the time of the first visit, the congregation was still meeting in the original building, constructed by the original Moravian visitors to the region in 1885. The building has held up well, but as the only evangelical church for hundreds of miles in any direction, the aging congregation wanted to construct a prominent new building for future generations. They also desired a larger space that would accommodate the growing Nepali immigrant congregation.

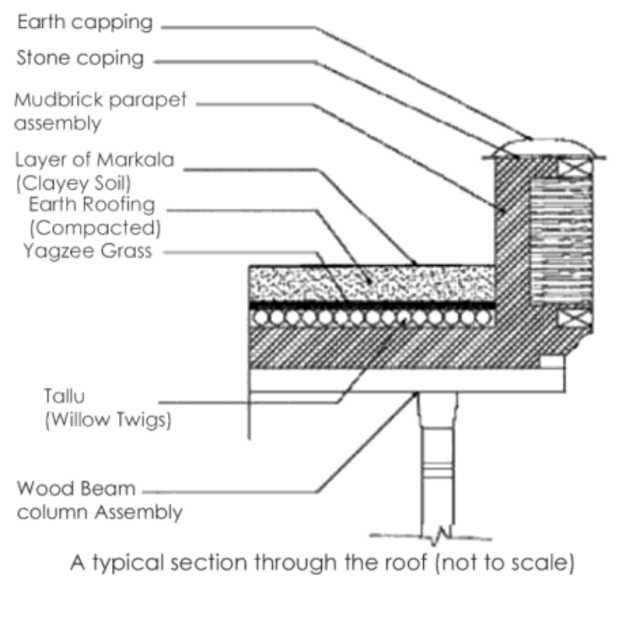

Leh is the economic capital of Ladakh, a region of north India inhabited by people of Tibetan descent. Situated in the Indus valley amongst the Himalayas at nearly 12,000 ft (over 3,500 m), Leh experiences long cold winters, but has abundant sunshine in its desert climate. Traditional Ladakhi building styles in this region incorporate thick stone and mud block walls, closely spaced timber columns, and a multi-layered wood and clay system called "Toksa" for floors and roofs. These buildings are warm during the long winter, and, due to good construction practices and the dry climate, last for centuries.Note 2

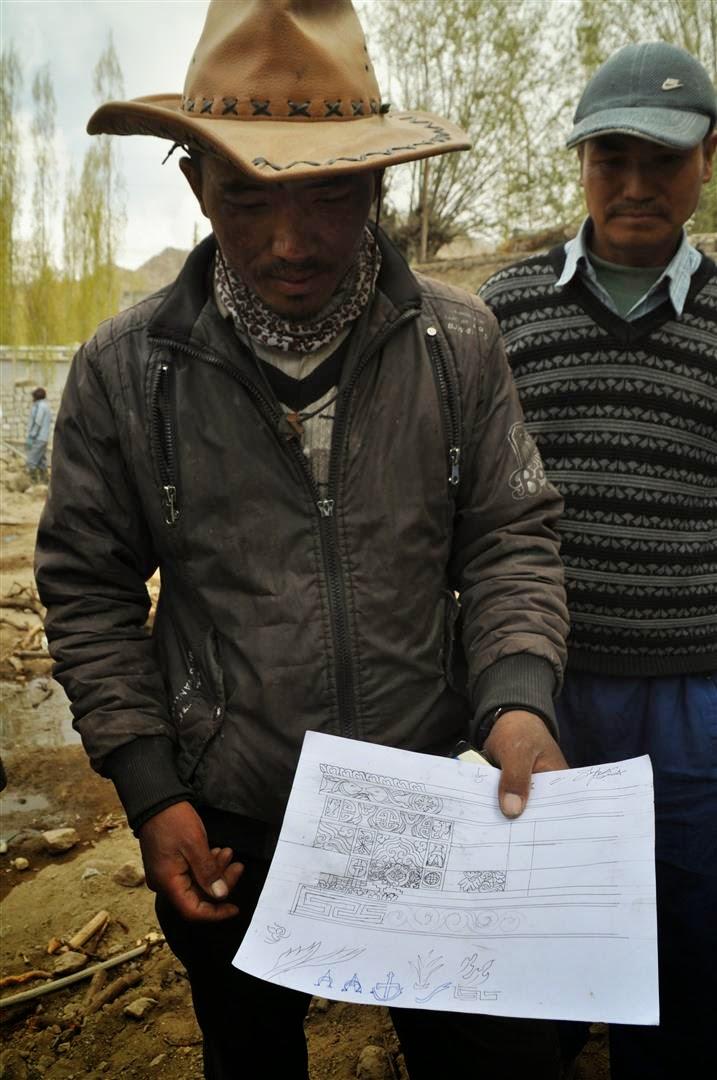

The 2006 concept design sat unused until 2012, when the land intended for the new building became free after having been squatted illegally on for many years. So EMI was re-engaged to provide detailed architecture and structural engineering for the building. During the design process, it became apparent that the congregation had differing opinions. Some church members wanted to build using traditional Ladakhi techniques, others wanted to build a modern concrete structure. A traditional building would be warm, and resemble other historic buildings in Leh, but would have low ceiling heights and tight column spacing that would restrict the church’s ability to utilize the space for large gatherings. A modern concrete frame would allow for better use of a larger floor space with taller ceilings, but would not be appropriate for the cold winters. And, unless careful attention was paid to the detailing of the concrete reinforcing steel, the building would lack the ductility to resist the expected seismic ground motions.

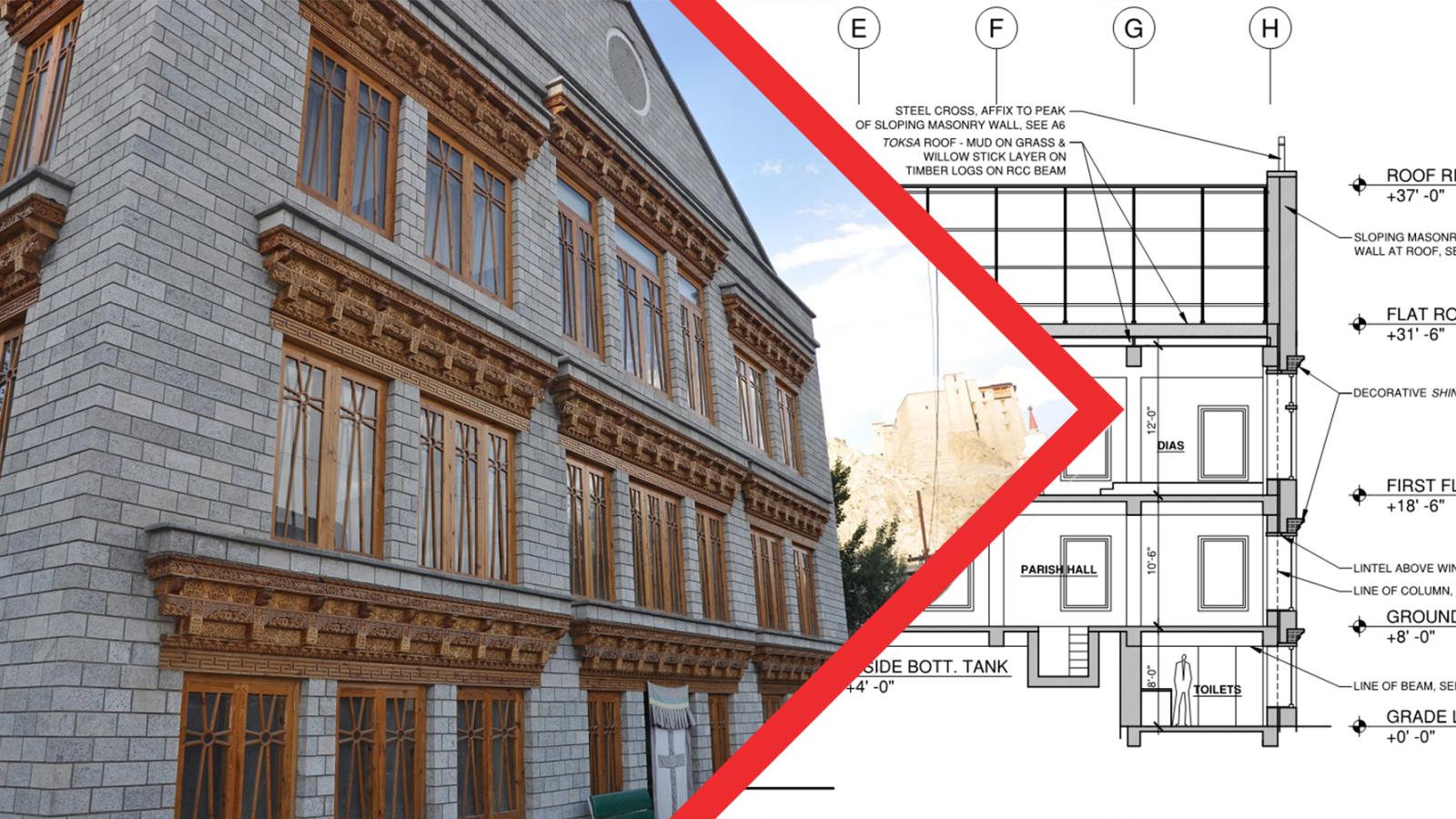

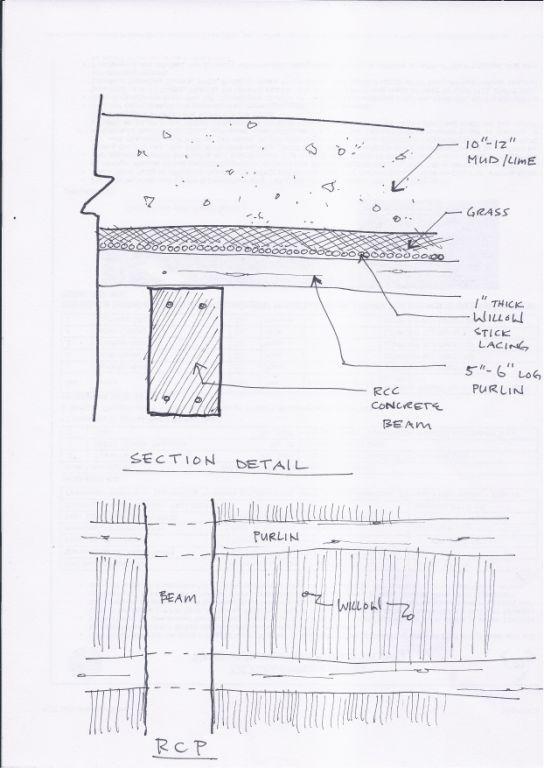

To resolve this and form a compromise, EMI proposed to incorporate elements of both building styles into one building; a kind of hybrid that meets both sets of goals as stated by the church members.Note 3 The design, finalized for construction in early 2013, is two stories with a partial basement, for a total square footage of nearly 11,000 ft2 (over 1000 m2). Construction began on schedule and was completed in 2015. Its structure is a reinforced concrete moment frame to provide larger column spacing in the sanctuary and community room. The exterior walls are a combination of double wythe stone and stabilized compressed earth block and a “Toksa” roof. The inclusion of the exterior stone wall and thick mud roof provides excellent insulation through the cold winter, but adds significant weight to the building, therefore increasing the seismic lateral force that must be resisted by the concrete moment frame. These heavy elements also require special attention to how they are anchored to the concrete frame.

The concrete moment frame is designed and detailed according to both Indian and Western seismic standards. Several key elements of this detailing include the close spacing rebar ties in the columns and beams, the rebar splice locations, and the development of rebar with 90° hooks. The double wythe stone wall lies completely outside of the concrete frame, while the earth block wall lies within the concrete frame. The two wall systems are tied together with a grid of timber lacing that is mortared into each wall. Additional anchorage of the stone wall is provided by rebar dowels embedded into the concrete beam/column joint that extend into the mortar between the two stone wythes.

The primary structural members of the Toksa roof system are 6 inch (15 cm) diameter round logs that are traditionally nailed to rectangular wooden girders spanning the columns. In this hybrid building, the wooden girders are replaced by concrete beams, so nailing the logs into the concrete is not an option. In order to provide lateral stability, a continuous angle was embedded into the top of the concrete beam, and the logs are notched to fit over the vertical leg of the angle. Without a reinforced concrete slab at the top level to utilize as a rigid diaphragm, a more heavily reinforced concrete frame than would normally be required for a building of similar geometry and loading became necessary.

This hybrid building design pushes the envelope for EMI projects in India. On most projects, EMI seeks to include no more than one or two new features or techniques for the contractor to incorporate during the construction. In the past, too many “innovations” have resulted in the contractor labeling the design as too complicated, and ignoring it to build something with which he is more accustomed. A multi-day pre-construction meeting between the designers, the pastor, and the masons went a long way in giving the builders the confidence to construct the building as designed. Communication back and forth between EMI and the contractor was not as frequent as hoped, but the project was completed in 2 summer construction seasons and inaugurated in 2015.

The Moravian Church Leh project is a great example of a client that values traditional building materials and techniques and also desires the benefits of more modern techniques. This experience further reinforces EMI’s goal of working with clients who view the quality and integrity of their building projects as a testimony to the communities in which they work.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.