EMI’s four-stage process for electrical engineering projects

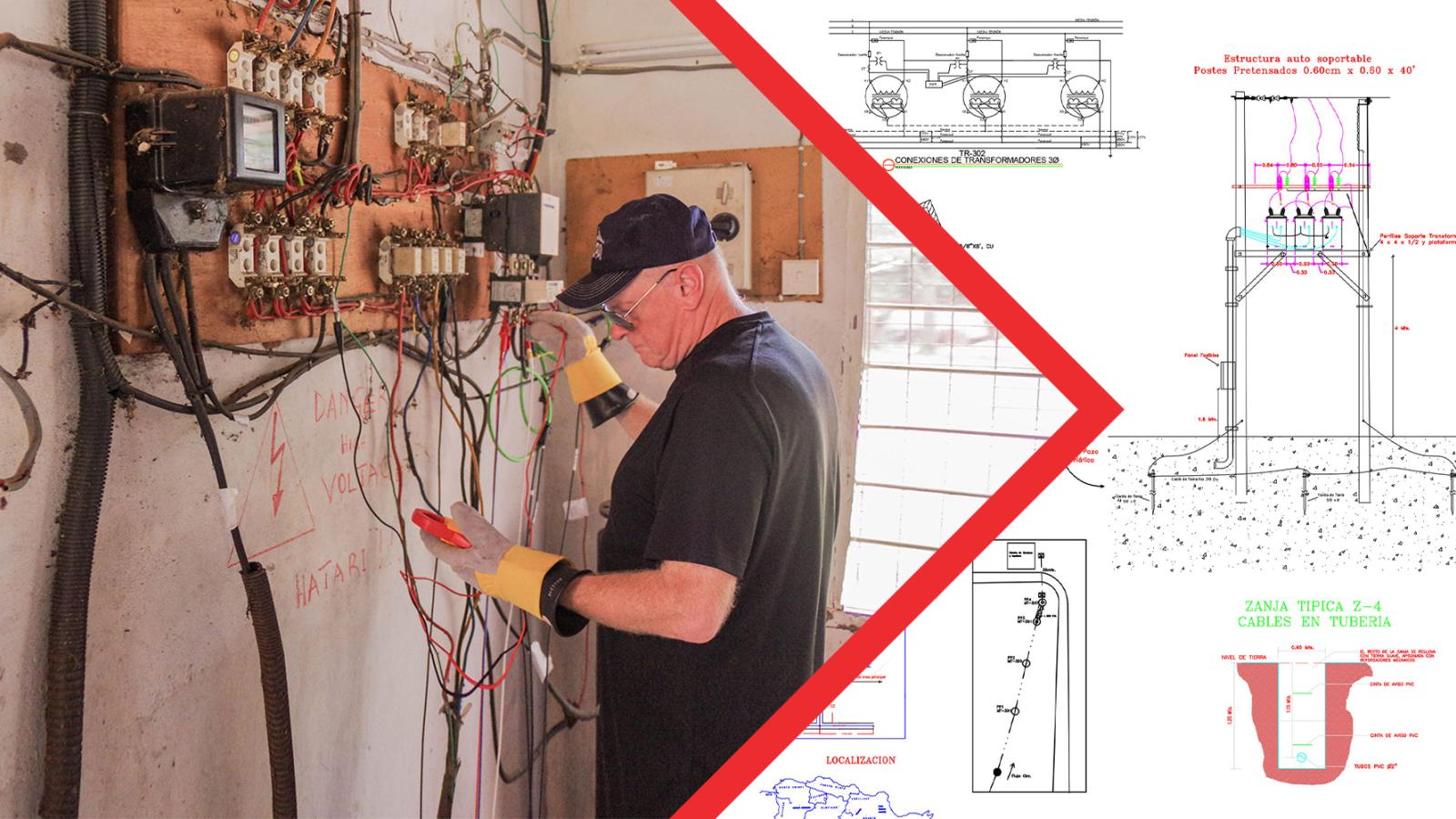

“You need to come see this!” exclaimed the EMI volunteer on the phone. The Electrical Engineers on our team hurried to the location on campus where smoke was rising from a small bush fire. An electrical fire had been started by one of the main campus overhead power lines. It had burned in half and was now laying on the ground. Maintenance workers had tried to hook up a welder which had overloaded the wire. As the cable fell to the ground, it knocked a man off his bicycle. Fortunately he was hit by the side that was no longer energized. By God’s grace, none of the other 2000+ students, staff, or workers on campus were seriously injured and the bush fire was put out quickly.

EMI had been asked to help this large ministry in southern Tanzania resolve their electrical infrastructure challenges. This incident underscored their desperate need. In many locations where EMI serves, electricity is an afterthought in the planning process and electrical systems are given little ongoing maintenance attention. In most cases there is a shortage of trained electrical design professionals and utility power can be unreliable and/or of poor quality. The result is facilities with dangerous and sometimes fatal electrical conditions. The following is an overview of EMI’s four-stage strategy to address dire electrical conditions in the developing world:

Stage 1: Assessment and Recommendations

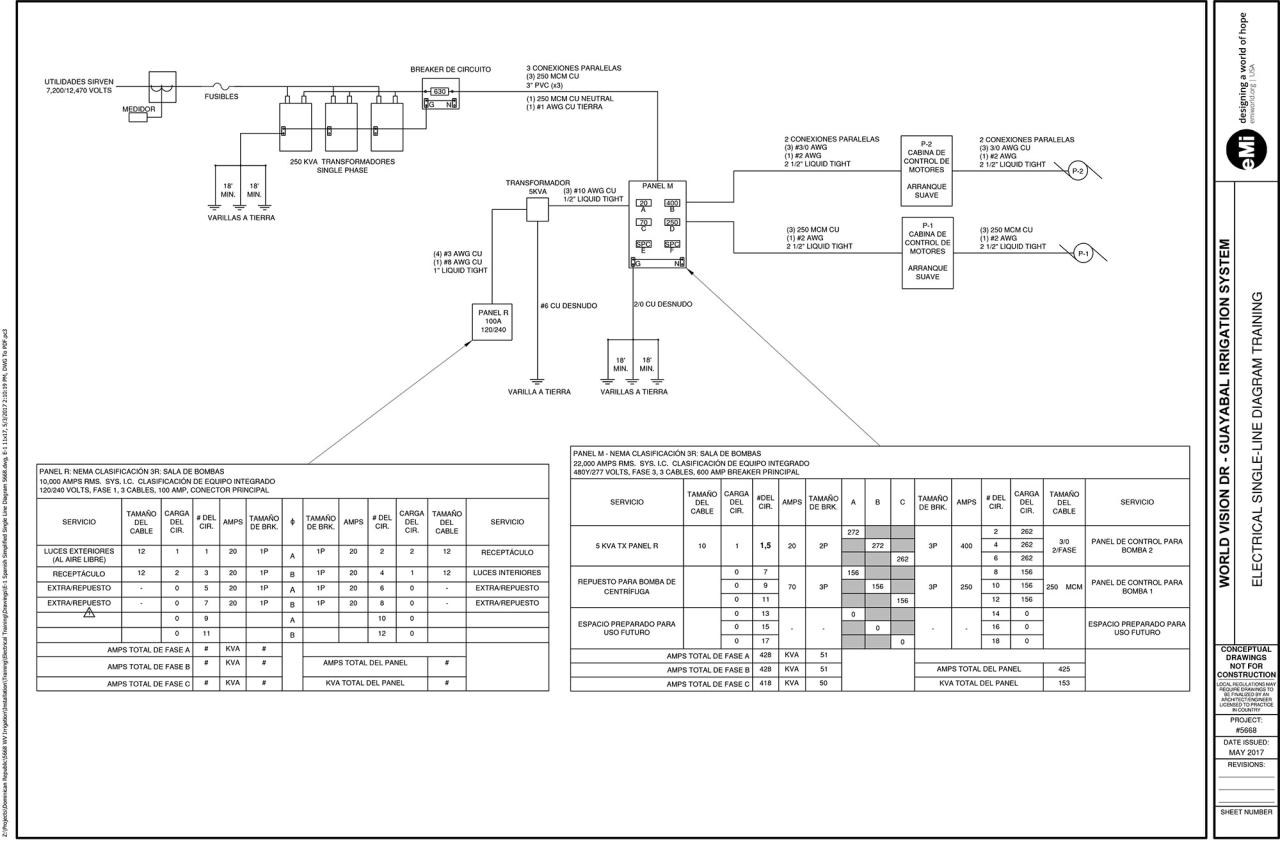

On any EMI project trip, an Electrical Engineer is often a critical member of the team. This is especially so on sites where an assessment of existing facilities is needed. However, many EEs do not feel technically competent to participate on EMI trips because of a career in computer programming or electronics, rather than power systems or facility electrical planning. Because of this, EMI’s Electrical Design Guide was developed to enable any Electrical Engineer to produce a good assessment and conceptual design for an EMI project. This Design Guide provides templates such as Load Study Spreadsheets, Single Line Diagrams, Electrical Legends, Panel Schedules, etc. to help the engineer get started while ensuring consistency and excellence in EMI electrical design and recommendations. Additional tools such as recording power analyzers, ground testing meters, and thermal imaging cameras are available at EMI for assessment projects. Assessment, conceptual electrical design, and/or any improvement recommendations are the elements of Stage 1.

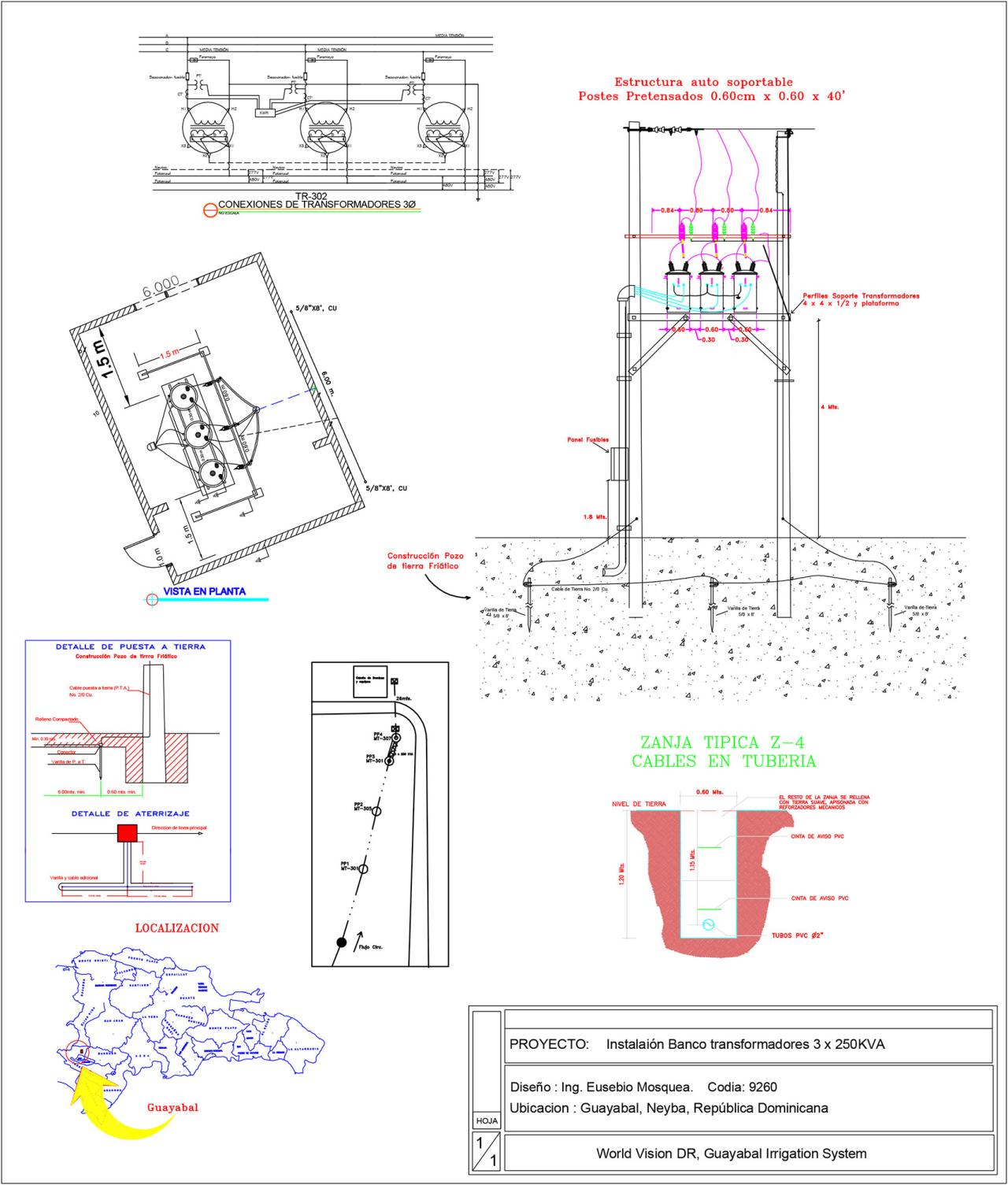

Stage 2: Design-Build Firm Selection, Detailed Design, and Installation

Once Stage 1 is completed, a detailed Scope of Work is created. Along with conceptual design drawings, the Scope of Work is given to local electrical design-build firms for them to submit bids for detailed design and installation. The goal is to identify a capable design-build firm as close to the site as possible which shows an ability and willingness to learn – even if they haven’t done a project like the one being proposed. EMI works with the client ministry to interview design-build firms, selecting the most competent one based on interviews and the submitted bids. Once the design-build firm is selected, EMI electrical staff and volunteers work with local designers to review and approve their detailed electrical designs and schedules. Often a design must be adjusted to accommodate locally available materials. EMI spends significant time to coach these designers as they select the best redesign for the project. During installation, an EMI staff or volunteer will be on site at critical junctures to ensure the design is being followed and that the quality of the installation is acceptable.

EMI makes an extra effort to identify and partner with local design-build firms for several reasons: 1) A local design-build firm will use equipment and materials that can be sourced locally. A system will be most sustainable and reliable if material & spare parts for repairs are readily accessible. 2) EMI has the opportunity to share knowledge and expertise with the local designers in order to build their capacity. 3) EMI learns what a realistic electrical design looks like for that region, and also what strengths and weaknesses of local electrical designers are. 4) The client ministry has a technical advocate in EMI who can ensure that their goals are accomplished and costs are kept within budget. 5) Because EMI invests time and knowledge in a local contractor, the client gains a competent local resource to help troubleshoot and maintain the system once it is operational. The overall objective is for the client ministry to look to their maintenance staff and the local contractor for ongoing system maintenance & operation, rather than being dependent on EMI.

Stage 3: Train Local Maintenance Staff

The goal is to leave the client ministry with a reliable, sustainable, and locally-owned system. This means the people operating the system need to understand how it works and how to keep it maintained. Many maintenance personnel at typical EMI project sites have had minimal technical training and often have limited formal education. Installation projects, therefore, are a significant opportunity to train members of the maintenance staff. EMI prepares and presents these training events using “Orality Principles.” This is due to the fact that most trainees would prefer to communicate orally, as opposed to communicating through written text. To communicate technical information using orality principles, EMI uses a variety of techniques including simplified drawings, stories, pictures, videos, analogies that trainees can relate to, hands-on workshops, and a lot of repetition.

For example, each trainee is given a set of flashcards with pictures of the different parts of the system. On the reverse side is a brief description of the important features of that part. The important features of a particular card are taught and repeated. Then, to test comprehension, trainees are asked to teach each other. Peer teaching is another effective tool for oral cultures because most are also collective cultures which share and own information as a group. EMI has found that oral-based trainees engage well with this method of training and can learn the material quickly.

Because the EMI team spends so much time during this process with the designers and on-site with the maintenance staff, there are unique opportunities for personal interaction. The hope is that EMI’s impact is eternal – not just limited to the life of an electrical system to be designed and implemented. Beyond the technical knowledge that might be gained through interaction with EMI, the goal is to share our hope in Jesus and give people an eternal vision for their lives with the Lord.

Stage 4: Evaluation

After the new system has operated for several months, EMI can send a volunteer to the site. This is to ensure that the system is operating as intended and to provide any further training needed by the maintenance staff. In addition, design-build firms are asked to include a 3-5 year maintenance plan in their quotes to cover going back to the site and fixing any issues that may arise.

Calling Electrical Engineers

Currently, EMI has only one full-time electrical engineer and one part-time electrical engineer on staff. Many ministries are showing interest in having EMI serve them in this capacity, and this work strategy could support two or three more full-time electrical engineers at EMI. Another need is for volunteers who can commit a few hours each week to review drawings and participate in conference calls with local designers. Consider using your EE skills for an eternal investment in design professionals and maintenance staff around the world!

Contact Andy about EE at EMI: andy.engebretson@emiworld.org

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.