When I first volunteered with EMI, I saw the importance of testing water firsthand. We were designing a master plan for a 26- acre Bible school property in Samfya, Zambia. There were numerous local water resources—from a municipal supply to an onsite borehole to a beautiful lake that adjoined the property. Our team came in with preconceived ideas about these sources and the ministry also had their own, differing thoughts. Water test results brought much needed clarity to the discussion and ultimately affected what we agreed on for the best water source and treatment solutions. The following article by EMI board member and volunteer, Rod Beadle, highlights some of the key objects to consider when testing water in the developing world.

—Jason Chandler, EMI WASH Ministry Program Manager

Why We Test

Water testing is a critical element of most EMI trips. The quality of water directly affects the health and well-being of the people within the ministries and communities that EMI serves. Water is the ultimate solvent. A wide variety of elements, some harmful and some beneficial, can be found dissolved or suspended in water. Understanding the contents and concentrations of potential pathogens and other elements in a given water supply allows for informed choices when selecting water sources and methods of treatment.

What We Test

In the developing world context, testing is typically done for various chemical, physical, and biological parameters to establish the relative quality of the water source. The local and national government water quality standards for the project area should always be researched. However, the most commonly referenced standards and limits are provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Chemical Parameters

When analyzing the chemical content of water, the focus should be on elements that are harmful to human health and elements that are added to the water to improve its quality. If it is not certain which chemicals may be present, use of an in-country water-testing lab should be considered. This is especially important if the project is in an industrial area or near heavy mining activities.

- Arsenic and Fluoride are naturally occurring chemicals found in groundwater which can be hazardous to human health at certain levels of exposure. These chemicals are regional problems, so it is important to verify whether they are a concern before visiting the field.

- Nitrates are a health concern because they can be converted into nitrites in the human digestive system. These nitrites can be toxic, especially in infants. Nitrates are often found in agricultural areas where fertilizers are used.

- Chlorine is not usually naturally occurring but is commonly added to water supplies as an oxidant to kill microbial contaminants. To be effective, free chlorine (not total chlorine) should be present at 0.2 to 0.5mg/l. At higher levels, water taste can become an issue.

Physical Parameters

The physical parameters of water relate less to human health, but can have other adverse effects.

- The pH of water has a strong influence on the effectiveness of chlorine and other disinfectants. Ideally, the pH should be between 6.5 and 8.5.

- Hardness and Alkalinity are closely related and tend to be higher in areas of limestone or dolomite. Hardness can cause scaling and soap-foaming issues. Alkalinity is an indication of the ability of a solution to resist changes in pH.

- The levels of Salt, Conductivity, and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) are separate parameters which are closely related to salt content and affect the taste of water. If the taste is too salty, many people will opt to drink from a more contaminated, but better-tasting water source.

- Turbidity is the measurement of cloudiness in the water resulting from visible particles. The level of turbidity is critical to determine whether filtration is required for disinfection to be effective.

Biological Parameters

Microbial contamination of drinking water is the primary cause of many gastrointestinal diseases. The most dangerous pathogens are spread through drinking water supplies that have been contaminated by animal or human waste. It is especially important to be able to identify and treat biological contamination.

It is not practical to test for all harmful microorganisms. Instead, biological testing relies on indicator organisms. Coliform bacteria are present in all animal waste and E. coli, a subset of coliforms, are present in all human waste. When coliform and E. coli colonies are found in water samples, it is likely that the water has been contaminated and that other, more dangerous pathogens are also present.

How We Test

Laboratory testing is often not possible when travelling. Fortunately, field-testing methods and equipment have improved in recent years so that the most important parameters can be accurately established at or near the source.

For testing chemical and physical properties, there are various testing strips, colorimeters, and electronic sensors that can be used. Cost, complexity, accuracy, and portability are the primary factors used to determine the appropriate tests to use.

In the past, microbial testing could only be accurately performed under controlled conditions in a laboratory setting. However, new tests have been developed that allow this testing to be performed in the field as well. WHO and EPA standards allow no coliform or E. coli colonies in a 100ml-tested sample for it to be considered safe. This can be a very difficult measure to achieve in the developing world context.

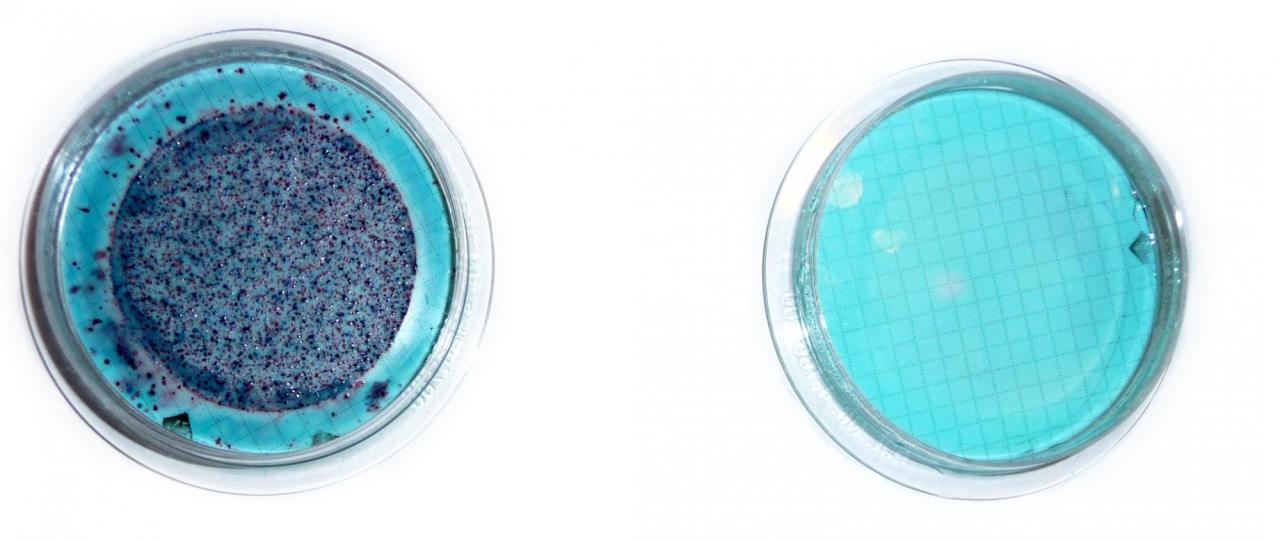

EasyGel and Petrifilm are field tests EMI commonly uses to test specifically for coliform and E. coli. These tests use a smaller sample size (5ml for EasyGel and 1ml for Petrifilm). In both cases, when placed in an agar dish at tropical temperatures, coliform colonies produce a red waste and E. coli colonies produce a blue waste within 24 hours. The red and blue colonies can then be counted and multiplied by the appropriate factor to get the corresponding number of colonies per 100ml. These tests determine not only whether the water is contaminated, but also evaluate the level of contamination. The primary limitation of these methods is that they do not test an entire 100ml sample, so some contamination can be missed.

How We Use Test Results

Care must be taken in how water test results are shared and with whom they are shared. It should always be remembered that EMI is neither credentialed nor qualified to conclusively state that a source is completely safe to drink. Also, sometimes there are necessary compromises that are made in the field which could affect the reliability of the test results. However, when properly performed, testing results—especially microbial results—can provide clear and compelling evidence of relative water quality. It is this evidence that leads to more informed and appropriate design decisions.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.