Exploring how EMI improves its design to be more appropriate for the end user

One of the most difficult aspects of work in the developing world is evaluating the appropriateness of the design. Does the design meet the needs of the ministry in a way that is suitable for the climate? Is it affordable to build through the use of local materials and construction methods? Is it clear to the ministry and their partners how to use and maintain the structures or infrastructure? The cultural perspective of the persons working in, using, and living in such a structure also influences their view of the effectiveness and quality of the design. A design can be effective in many ways, but if it does not adequately consider how the building will be used and by whom, it might create problems for the users.

One tool the EMI Uganda office uses to learn what design features work well, and where we can improve our design process, is to perform what we call a “Post-Occupancy Assessment.” This type of review involves EMI personnel returning to a project that has been designed and built by EMI and assess how successful the design has proven to be once it has been used by the client for a number of years. The typical assessment process involves reviewing EMI design drawings, then visiting the project site to inspect the buildings and interview the building’s users, management, and maintenance personnel. We review with the client what has worked well, and any problematic aspects. Over multiple assessments, we look for trends, both positive and negative, which help prioritize what elements to focus on in upcoming designs.

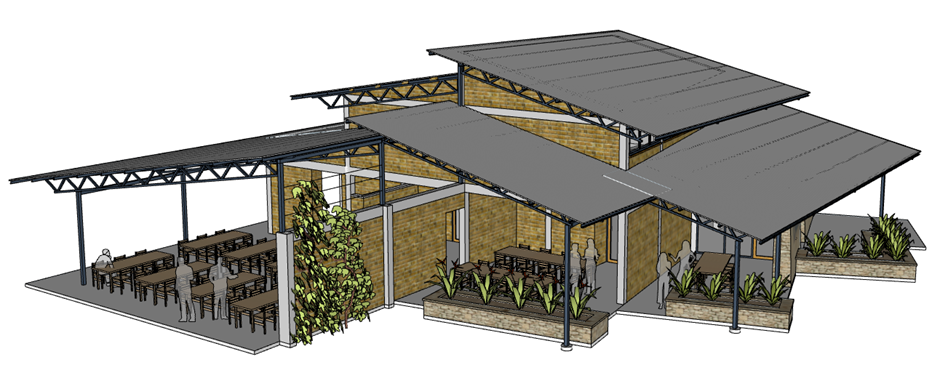

Most of our clients’ responses have been overwhelmingly positive regarding the design and construction work by EMI. We received many comments such as “It’s hard to think of anything better than this” or “We love the open layout and natural lighting.” One design feature that seems to be appreciated across multiple clients in Uganda is covered spaces with little to no walls. We have found that these types of areas are used for many more activities than which they were originally designed. For example, administrators chose to leave the designated meeting rooms inside a building to meet in covered outside spaces that were originally designed for other purposes, such as open eating areas. This feedback on how spaces are used has helped inform current designs.

However, the process of post-occupancy reviews has also identified a number of situations where past EMI designs were not completely appropriate for the users. One such case was at a medical clinic EMI designed and built. It was found that the original client-approved design did not provide adequate privacy for certain operations such as triage and phlebotomy. The original design was based on the use of moveable partitions which enhanced flexibility; but after using the facility with such partitions, the medical staff observed that more privacy, as well as better sound insulation, was needed to make the patients comfortable while undergoing these procedures.

Additionally, in their medical laboratory, the clinic had coated the porous dark gray concrete counter tops EMI installed with a white epoxy coating to make clean-up easier, and help keep the laboratory more sanitary. This showed us the importance of gaining a better understanding of the way the buildings we are designing will be used. In this case, because the ministry had not yet employed medical staff, we could have sought more medical personnel feedback in the initial design process.

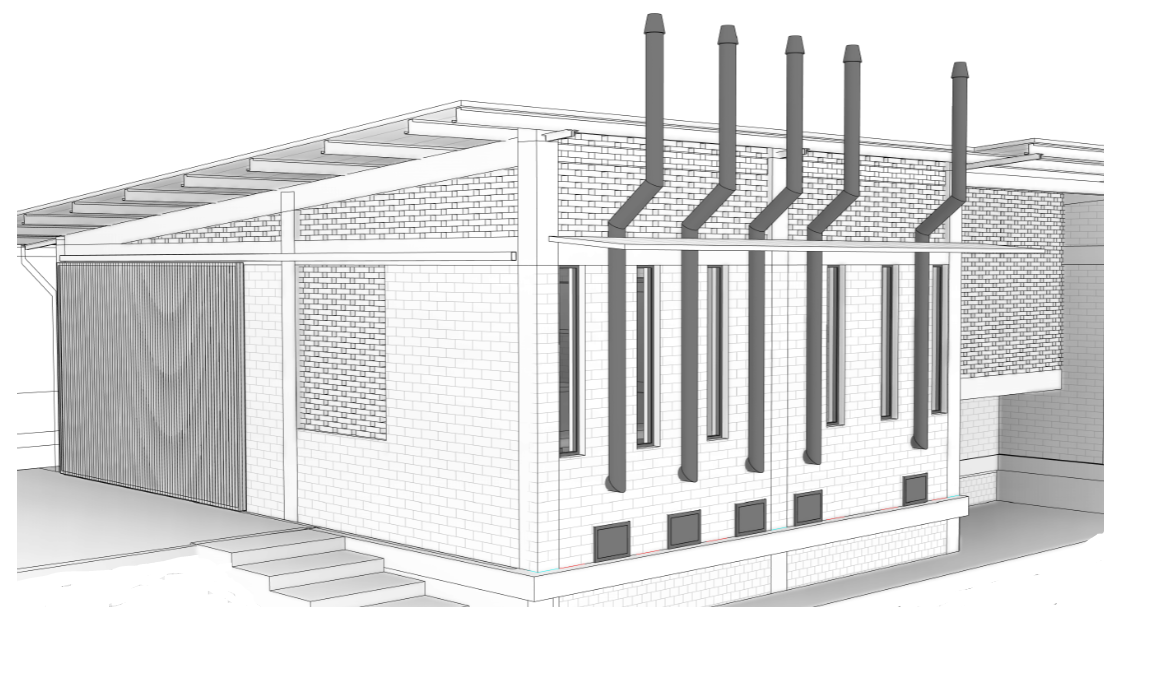

In post–occupancy assessments at a couple different sites, it was seen that the kitchens, which use fire wood to cook, were very smoky and the interior walls and ceiling covered in soot. Part of the reason for so much smoke inside the building was due to the fact that, while EMI assumed the fire chamber doors would be kept closed during operation, they were in fact always open during operation. When Ugandan’s use firewood to cook in their homes, they do not chop the wood into small pieces, but rather slowly push long pieces into the area where they are burning. EMI assumed the wood would be cut into short pieces, placed in the fire chamber, and the door shut. However, even though the stoves were different, the cultural practice of cooking over firewood continued, and the uncut long pieces of firewood were placed into the fire chamber, slowly being pushed in as they burned, necessitating the door remain open.

From these observations, EMI Uganda is making modifications to the kitchen layouts. In a current design, the fire chamber doors have been located on the outside of the building rather than the inside. Provision for additional ventilation has been added, and there is more of a separation between the cooking and serving areas. We’ll follow up in future assessments to see the effect of these changes.

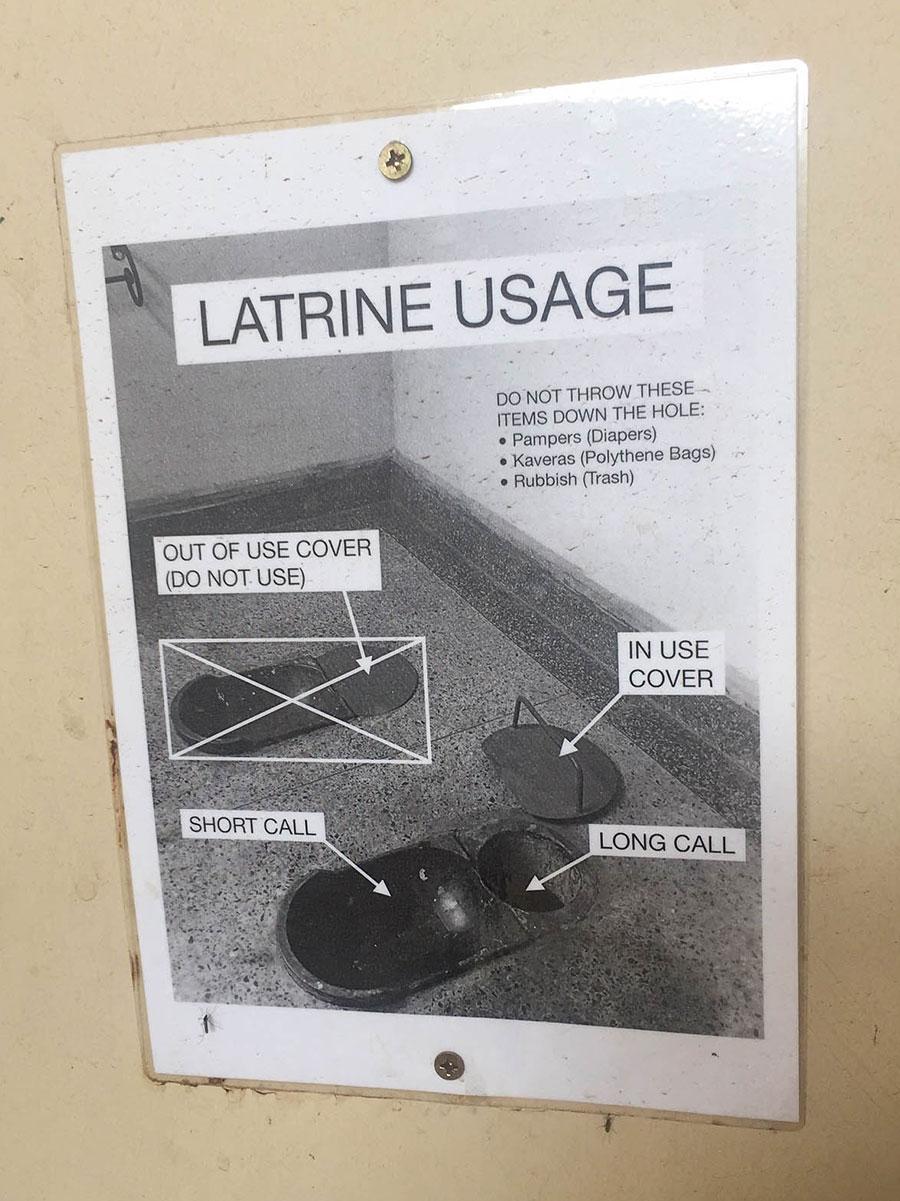

During another post–occupancy review at a large secondary school we observed that EMI designers chose to install dual pit ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines for students and visitors. These latrines have two identical pits for each stall, which requires two toilet pans, but only one should be used at a time. The two pits allow the first pit to be sealed off when it is full so waste can fully decompose. These VIP latrines have the added feature of urine diversion to reduce the load of liquids introduced into the latrine pits, which should improve the decomposing process, and reduce odors and insects. To make this system work properly, special latrine pans are required. The use of two special urine diverting pans make this type of latrine complicated and very different from latrines most people in Uganda are familiar with. We were told that this system works for students, once they are suitably trained. However, when family members, guardians, and friends visit the site, there are problems with plugging of the latrine pans used by the visitors. To alleviate this problem, the school has prepared an instructional poster and placed it in the latrine, instructing users on the proper use of the unfamiliar latrines. They also post a student outside the latrines to help those unfamiliar with this type of latrine on its proper use. This illustrates the complexity of a solution working for one group of people, but not all groups which may use the same facilities.

In additional follow up conversations, it was seen that the dual pit feature was not being used as designed and was unnecessarily complicated and expensive. As a result, the design of future latrines has been changed to use only a single pit and toilet pan, simplifying use and reducing cost.

As we conduct these inspections, we are in the enviable position of having “twenty-twenty hindsight”; we are able see what works well and what could have been designed better from the user’s perspective. As can be seen in these examples, issues arose out of different cultural practices. Over time, these types of assessments can help us better understand, not just technical solutions, but culturally appropriate solutions for clients in East Africa. The perspective we gain during our post construction assessments gives valuable insights to our design personnel to continually improve the appropriateness and technical adequacy of our designs.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.