Discovering how much groups define our sense of worth, social role, and security.

It was morning in East Africa. A team of EMI designers disembarked from the land rover, excited to return to the site. Last year they had come to survey the land and design the first building: phase one of a new hospital. The team had worked hard to give Moses, the ministry leader, a plan that was beautiful, practical and cost-effective. Now they would see the fruit of their work.

Yet as they entered the construction site, a surprise met their eyes. The building floor level was some three feet higher than designed, necessitating stairs and a steep ramp. Mike, the EMI project leader, was a civil engineer who had developed a good relationship with the ministry over the last two years. He turned to Moses with a questioning look. Moses offered an explanation: “When we started construction, some friends of the ministry raised concerns about flooding.”

Over the week, the EMI team urged Moses to return to the original design. “The data from the survey and soil tests indicated that flooding will not be an issue. Raising the structure unnecessarily increases the cost. The steep, makeshift ramp will be challenging for patients.” Yet each time Moses politely deflected these attempts, deferring to other, unidentified advisors…

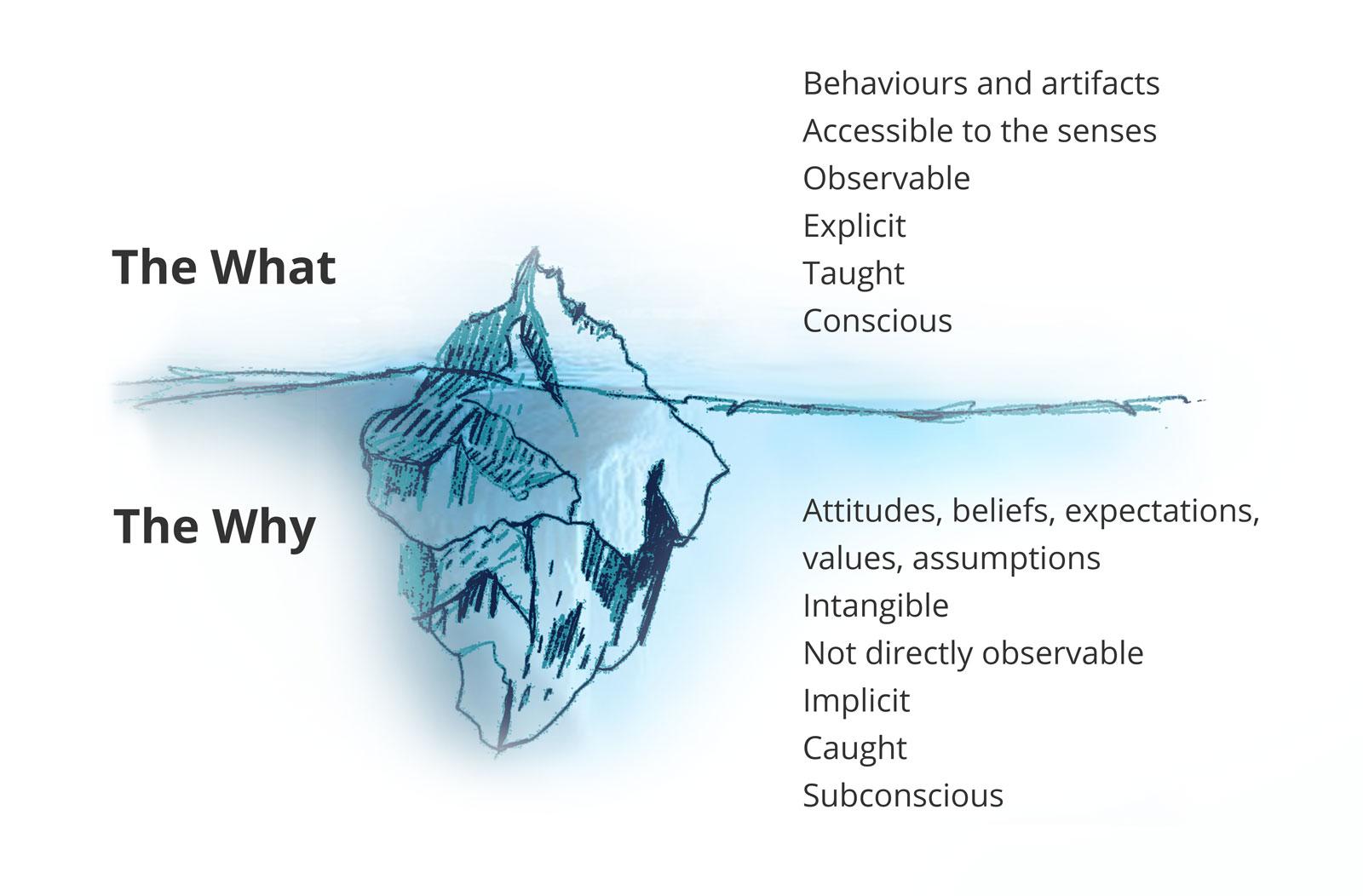

In my first article, I introduced the cultural iceberg concept: An idea that culture exists both above the waterline and below. Above the water is The What, or that which we can observe with our senses. Below the water lies The Why, or the intangible, subconscious aspects of culture. These include attitudes, beliefs, expectations, values, and assumptions. This greater mass of culture lies beneath the waterline, and we must go out of our way to recognize and understand it.

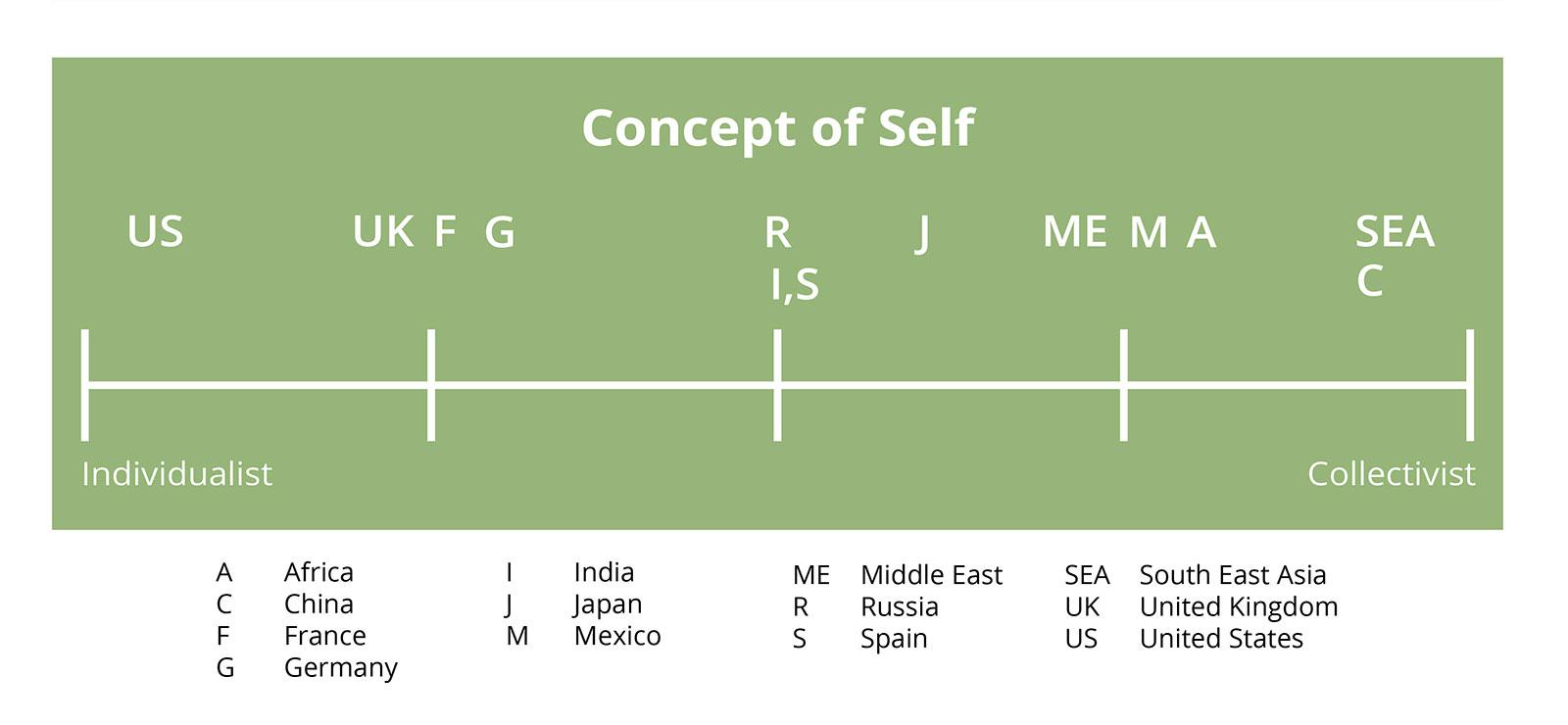

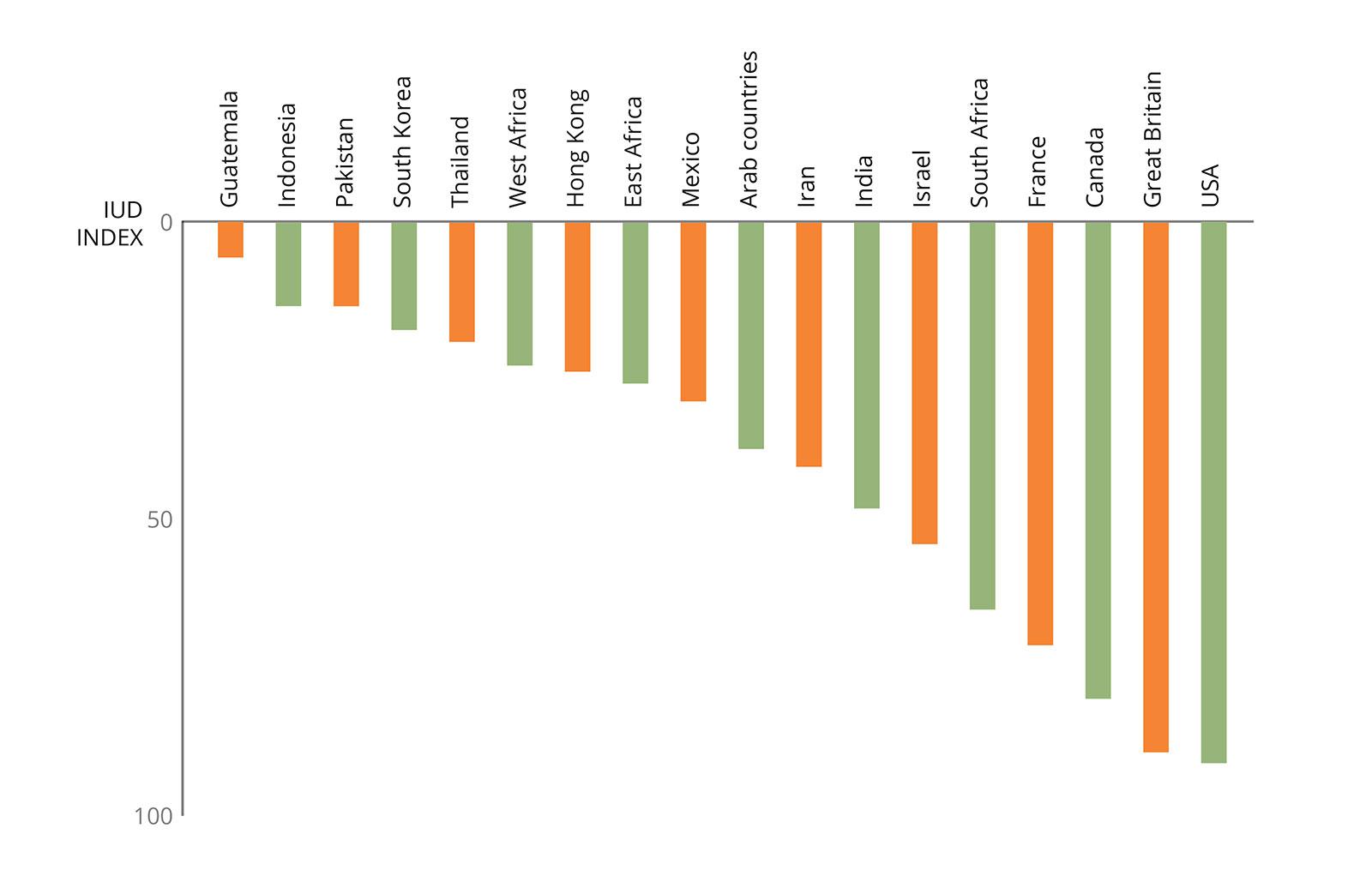

Culture specialists often explore a particular aspect of culture in terms of a spectrum or continuum of values (Hall; Hofestede; Storti). These continua are useful tools for comparing the general values of one culture to another. My second article focused on communication: How words and context are used to communicate truth. In this final ‘Iceberg’ article, we will look at identity: How do I understand who I am?

Every person everywhere belongs to groups. At the very least, we all have family, ethnicity, and nationality. The identity aspect of culture explores how much we look to our various groups for our sense of worth, social role, and security. How tight or loose are our social ties?

From birth onward, members of collectivist societies are integrated into cohesive in-groups that protect them throughout their lives in exchange for loyalty and service. The most-immediate group is the family, which includes parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles, and in-laws. This group can extend to members of the same clan, tribe or ethnic group. Other groups may include “age-mates”, members of a religious community, or employees of the same company.

Within the collective, roles are clearly defined. The group tells the individual who they are and what they are expected to do. Social ties are strong and endure. Societies tend to be more stable and conservative. Opinions on any given topic are determined by the group and do not tend to change quickly over time. An individual’s security lies in serving and being served by the group. There is no “I” apart from “we.” Most people of the world live in collectivist cultures. This includes the vast majority of Asians, Africans and Latin Americans, as well as parts of southern and eastern Europe and several North American subcultures.

Individualistic society is the opposite. The interests of the person take priority and social ties tend to be flexible and impermanent. Family is usually defined as parents and children only. In-groups are usually joined by choice and last only as long as they suit the needs of the individual. In the end, each person is expected to be responsible for him- or herself. Terms such as “self-image, self-reliance, self-confidence, and self-awareness” are commonly used. North Americans and northern Europeans tend to be on the individualistic side of the spectrum.

A culture’s proverbs are often revealing expressions of its values:

Individualist

Live and let live.

To each his own.

To thine own self be true.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

Collectivist

No matter how stout, one beam cannot support a house.

Brothers and sisters are as close as hands and feet.

One piece of wood will not make a fire.

The chicken is never ashamed of its coop.

These two ways of approaching and valuing identity naturally lead to different behavior. In the workplace, collectivists tend to stick together. Often, children are expected to take up their father’s profession, and hiring is done from within the group. Salaries often go back into a communal fund, or those who earn more are expected to support those who earn less. There is often little separation between professional and personal spheres, since life is about caring for the group.

To the individualist, this “favoritism” or “nepotism” in hiring and the lack of control over “one’s own salary” can appear unethical or unfair. Clear boundaries between work and home are considered essential and extended family have no particular right to “my” money. Moreover, loyalty between employer and employee remains only as long as the relationship benefits both parties. Changing companies and moving away from family to pursue a job are seen as legitimate ways to advance in life.

Friendship is also defined differently on the two ends of the spectrum. For an individualist, friends come and go relatively easily. Cordial interaction over a short span of time can be sufficient for an individualist to call another person a friend. However, even if two people have been friends for many years, it is usually considered inappropriate to make large requests or ask very personal questions. Moreover, if one moves away or interests change, the friendship can fade without hard feelings.

On the other hand, when a collectivist person calls another a friend — i.e. a member of the in-group — the implications are deep and long-lasting. That friendship is expected to be permanent and sacrificial. We could avoid many cross-cultural misunderstandings if we understand what friendship means within a culture. On a short-term trip, for example, an individualist traveler may feel like he has made many new “friends”, while the collectivist host may see the visitors more as “contacts.” To call them friends would move them into an entirely new category with different expectations.

With these ideas in mind, let’s revisit Moses and Mike. Though Mike provided Moses with expert advice and concrete data, Moses proceeded with the modified plans on the advice of others. Why? What was happening below the surface?

After two years of cordial interaction, individualistic Mike probably considered Moses a friend. Moreover, Mike was an engineer and believed that his expertise regarding flooding should carry more weight than the opinion of a layperson. However, Moses the collectivist was using a different scale to weigh opinions. He valued his relationship with Mike and the expertise of the team. However, Mike was not a full member of Moses’ in-group. Moses needed to weigh the additional cost of construction and the cost of offending Mike against the cost of going against the wishes of his in-group. In the end, Mike and the team would go home, but if Moses offended his in-group, their support of his ministry might be jeopardized.

As a skilled leader in his own cultural context, Moses was performing a balancing act behind the scenes, which Mike did not see or understand. As with so many cross-cultural interactions, what lies below the cultural waters is what really counts.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.