Navigating differing communication styles & cultures in design

It’s a balmy day in one of India’s oldest cities. Our EMI project team—a mix of North Americans and Asians—is gathered around a conference table as we eagerly share the latest iteration of our master plan for a new training center. The clients are a married couple, Indians who have given up lucrative careers to work in a difficult and sometimes hostile region. As the project leader lays out the trace paper and begins his presentation, I watch the clients carefully. The husband leans in to listen. The wife sits back, arms folded, legs angled toward the door. Both are nodding and smiling. Both say they like the new draft, but I’m not so sure.

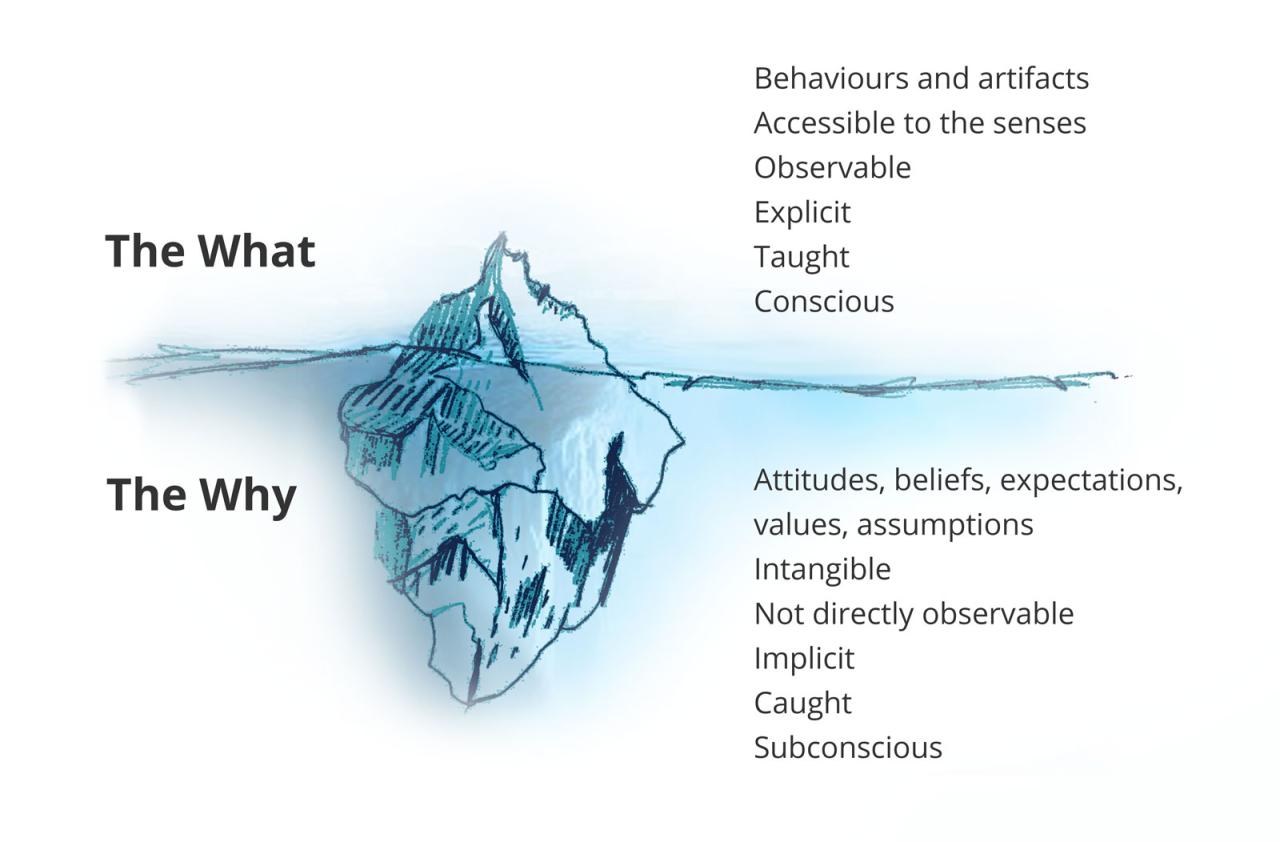

In my last article, I introduced the concept of the cultural iceberg: the idea that culture exists both above the waterline and below. Above the water lies The What: that which we can observe with our senses. Below the water is The Why: the intangible, subconscious aspects of culture which include attitudes, beliefs, expectations, values and assumptions. The greater mass of culture lies beneath, and we must go out of our way to recognize and understand it.

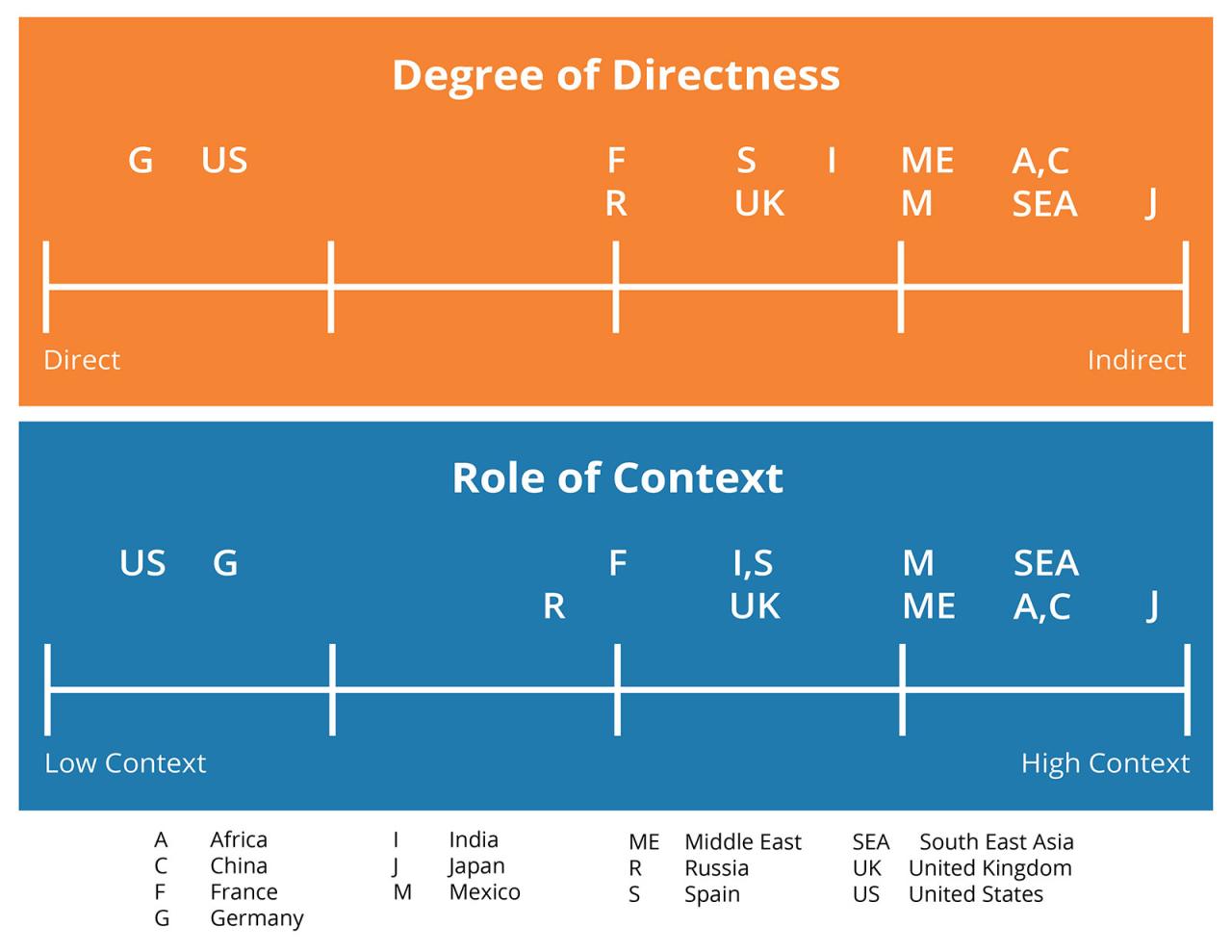

Culture specialists often explore a particular aspect of culture in terms of a spectrum or continuum of values (Hall; Hofestede; Storti). Though individual preferences within a society do vary, these continua are useful tools for comparing the general values of one culture, relative to another. Some of the more commonly discussed values continua include Individual vs. Collective, Egalitarian vs. Hierarchical and Task-Oriented vs. Relationship-Oriented. In this article, we will focus on the area of communication: how words and context are used to communicate truth.

Every person from every culture communicates, both intentionally and unintentionally. Each of us uses a variety of means to do so – words, gestures, tone of voice, silence and touch. Even clothing, posture, and use of space and time convey a message. Experts estimate that anywhere from 70-93% of communication is nonverbal. With so many means of communication at our disposal, we have to choose which to prioritize when giving and receiving messages. Do we prefer to spell things out explicitly or do we let others read between the lines? Do we give more weight to words or to the context of those words? Our choices depend a great deal on our cultural background.

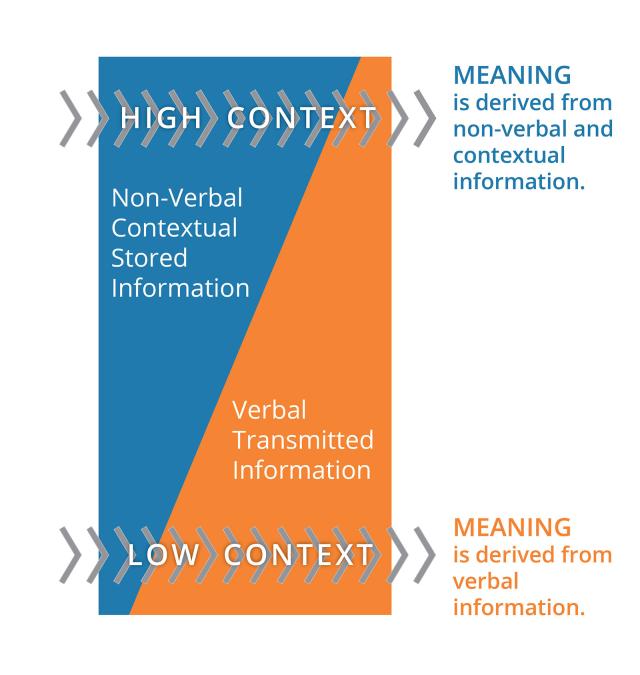

In a society where communities are close-knit and relationships are long-lasting, it is natural to rely on shared experience and mutual understanding to communicate ideas. In these High Context or Indirect societies, communication is usually indirect and non-verbal. Many things do not need to be spelled out explicitly. To be blunt might even cause offense, as it can imply a lack of respect or a desire for distance. Situationally, families and close friendships tend to be high context. Globally, most of Asia and parts of Africa, Latin America and southern Europe operate this way.

In a society where relationships are more transient and less holistic, where people have fewer experiences in common, it is more important to be clear, precise and explicit. To be indirect invites misunderstanding and confusion. Rather, the dictionary definitions of words are given priority over any nonverbal or otherwise indirect message. These cultures are called Low Context or Direct. Situationally, legal contracts, building codes and computer coding languages are good examples of very low context communication. Regionally, northern Europe and North America tend to be low context cultures.

At the heart of the issue of context lies a basic question: What are words for? Are words primarily for transmitting data? Or are words primarily for navigating and strengthening relationships? In high context, indirect societies, truth (i.e. data) is usually communicated nonverbally, while words are used as tools for affirming relationships.

To someone from a direct, low context culture, this can sometimes feel like lying. A classic example of this is the use of the word “yes.” For a direct communicator, the word yes is understood in terms of its dictionary definition. However, someone from an indirect culture may not feel free to use the word “no” because its inherent negativity might damage the relationship. So an indirect communicator might use the word “yes” to mean “yes, no, maybe” or simply “I’m listening.” The verbal “yes” affirms the relationship, while “no” can be clearly communicated nonverbally in other ways.

Consider the project meeting I described above. A team of experts has come to design a training center. They are guests of the client, and they have been working hard to produce high-quality designs. At the meeting, the well-mannered, hospitable clients can only appropriately respond one way when presented with the team’s ideas: “Yes, we like this!” Both husband and wife smile and nod and indicate with their words that they agree with the team. But one of the clients, at least, is indicating with her body language that she is not fully onboard. Her body posture is saying “I am really not open to this.” She may not even be aware that she is doing this, but another person from her cultural context could pick up on her signals and work to literally turn her back toward the group.

Fortunately, our EMI team did notice the signals and recognize the disconnect. During project meetings, we paid close attention to nonverbal cues, and asked open-ended questions so that we could better understand our client’s vision for the training center. During informal interactions (such as meal times or trips to and from the site) we looked for opportunities to build rapport and understanding on both sides. As we got to know our clients as people, we were better able to read their indirect and nonverbal signals. Likewise, they were better able to understand our communication styles.

When discussing the concept of indirectness, designers from direct cultures often express frustration: “Why won’t they just tell us what they think?!?” This question reflects a fundamental misunderstanding. Indirect communicators are often, in fact, very clearly expressing their ideas. They are just using a different method than a direct communicator would. To an indirect communicator, using only words to express ideas, emotions and desires can feel a little like painting a picture in black and white rather than in full color.

The clients in the above scenario had sacrificed a great deal for this project and were willing and ready to communicate their desires to us. We just needed to be tuned-in to their cultural way of doing so. By the end of the week, we were all on the same page, excited to move ahead with design and construction.

From its founding, EMI has worked cross-culturally to produce designs for use around the world. But the need for cross-cultural wisdom is ever-increasing. While the majority of EMI’s designers still come from low context, direct cultures, most of the people we serve communicate indirectly. Moreover, as we work to recruit more diverse teams, all of us must learn to see and understand culturally different communication styles. As we combine the strengths of both modes of interaction, the potential for relating and designing “in color” is truly exciting!

The Cultural Iceberg & Communication is the second of a three-part series exploring the cross-cultural dynamics of EMI’s ministry.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.