How EMI approaches flood risk assessments of EMI projects

Considering flood risk in our projects can seem like an un-necessary hurdle to jump in the permitting process. For our clients, it may seem like a distraction at best and, at worst, a huge cost in terms of flood management infrastructure. In many of the places EMI works, proper site grading plans, landscaping and water management are under-valued design services. Even in areas where local legislation does not require proper flood/water management compliance, we have an ethical duty to protect human life and enable communities to flourish. Flooding causes death, loss of home and livelihoods, risk of disease, and spread of solid waste. As many as 107,487 people died due to heavy rains and floods across India over 64 years between 1953 and 2017, according to Central Water Commission.Note 1 During this period, damage to crops, houses, and public utilities was reported to be 50.9 billion USD.

A Flood Risk Assessment (FRA) is the first step in flood management and includes an investigation of the source(s) and extent of the flood risk based on historic flooding records and theoretical modelling. In addition, knowledge of the local and regulatory context is required to understand potential man-made factors which may affect the flooding or potentially constrain the interventions.

Types of Potential Flooding Sources

|

Pluvial Often known as surface water from rain-fall |

Fluvial River/Tributary |

Tidal/Sea |

|

Utilities i.e. burst municipal pressurized water mains |

Resevoirs and Glacial i.e. burst dam, glacial lake ouburst |

Groundwater |

Flood Risk can be managed at the site level, but also the local, regional and national level. Where does EMI fit in? Although EMI has made successful contributions beyond the site level to impact whole communities (such as flood and erosion protection for an island community in the River Krishna and development of a Flood Resilience Strategy for a district in Bangladesh), predominantly, our sphere of influence and scope of work is related to the site level, with consideration of local factors. EMI projects typically are concerned with campus development in a defined plot of land, for which we are responsible for considering flood risk and developing good grading and drainage plans. At a local level, EMI investigates the external topography, hydrology, water courses and public drains that may affect the development.

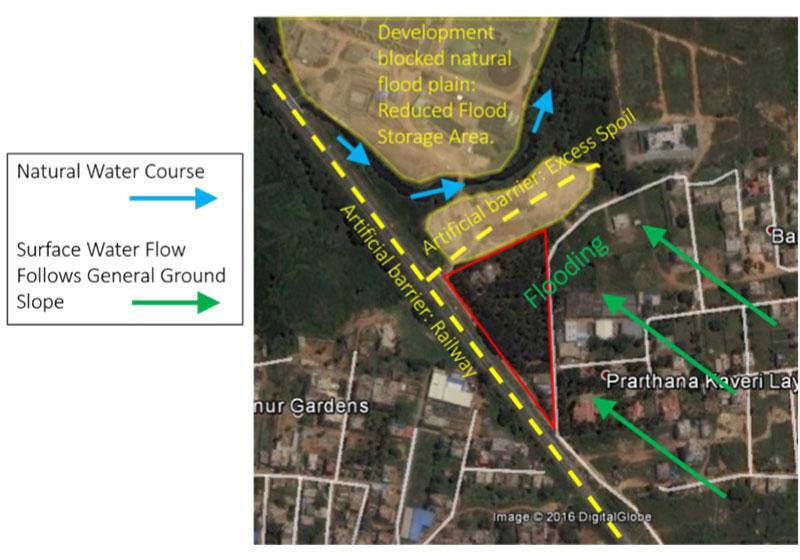

However, when planning a development, we must assess both the Flood Risk to the development and from the development, the latter being the less well known concern. In the absence of legislative enforcement, developers are likely to ignore the impact of their development on other properties or the wider environment. For a number of EMI clients in India, their properties have suffered increased flooding due to ill-planned development on neighbouring land. Using satellite imaging such as Goole Earth, we can track the impact of developments over the last 20+ years. From this we can see when a developer has ignored the natural flood routes and built up land which otherwise would be flood storage or flood conveyance.

New developments normally increase the impermeable surface area of the site compared to the pre-developed case. This results in an increased storm-water runoff rate. This increased rate can cause an increased flood risk in neighbouring properties/assets. However this can be managed, using attenuation (extra storage volume) and controlling the discharge rate using flow control technology.

Sources for Flood Risk Assessments

Given the importance of understanding the true nature of flooding problems, EMI uses a variety of sources for input.

Historic Flooding Data and Flood Mapping

The first point of reference for an FRA is a study of available flood data and flood mapping. Useful historic information could include photographs of notable events, rainfall data, river or tide level data and impact assessments. In some cases, flood maps created by government agencies to inform development strategies may exist. These maps have potential to represent all known flood sources and illustrate the level of risk using flood risk zones. The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) has developed flood warning maps which are kept up to date via river level gauges and a comprehensive river system model.

EMI India recently used historic river level data during a feasibility study for a client. The project was to construct a helipad at the side of a river in Manali. By reviewing the observed historic data and correlating this with reports from locals, EMI convinced them early on that this was not a feasible project and had huge environmental implications. Just a week after making this recommendation to the client, a flash flood event occurred leading to river bank failures and devastation of properties.

Theoretical Modelling

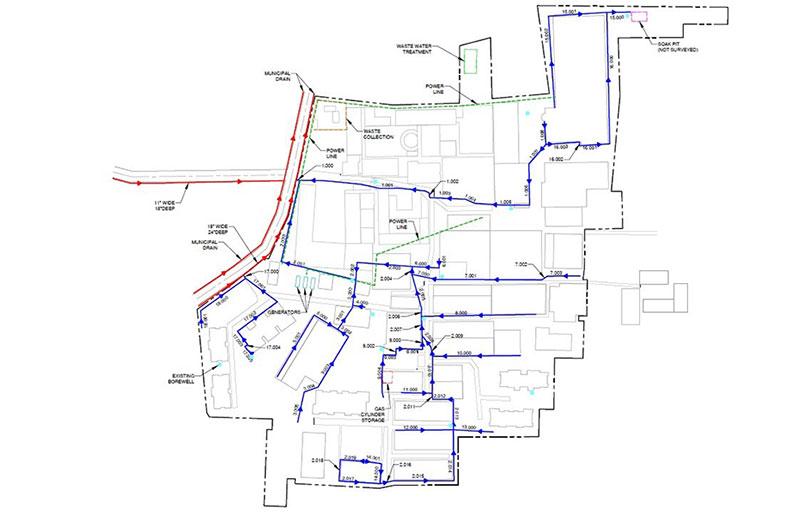

Theoretical modelling enables the engineer to predict the frequency, extent and magnitude of the flooding. Where it may be relevant to the development in question, river modelling may be done through the HEC-RAS programme. To model over-land flow and surface water flooding, Micro-Station is ideal. Storm and Sanitary (now part of the Civil 3D package) can be used to evaluate surface water runoff and the adequacy of drainage networks.

Hand methods using the rational method enable a reasonable estimate of peak surface water runoff. This method can be used in the absence of costly software and may be most appropriate as a quick check during a project trip. Ideally the engineer can calibrate the catchment runoff characteristics, by measuring the flow rate in a stream or drain and the associated rainfall intensity-duration data.

Community/Stakeholder Engagement

Theoretical modelling can only be as good as the source data used. Therefore it is beneficial to triangulate the theoretical predictions and historical data with anecdotal information from the communities directly affected by the flooding. This information can be obtained through large community gatherings or meetings with specific demographics within the community. This information adds to the overall picture about the extent and magnitude of flooding. However, it is also extremely useful to identify the vulnerabilities within the community and the impact to people and property. It is helpful to understand what the communities perceived challenges and needs are during the flood and the existing mechanisms and capacities within the community to respond to the flood event.

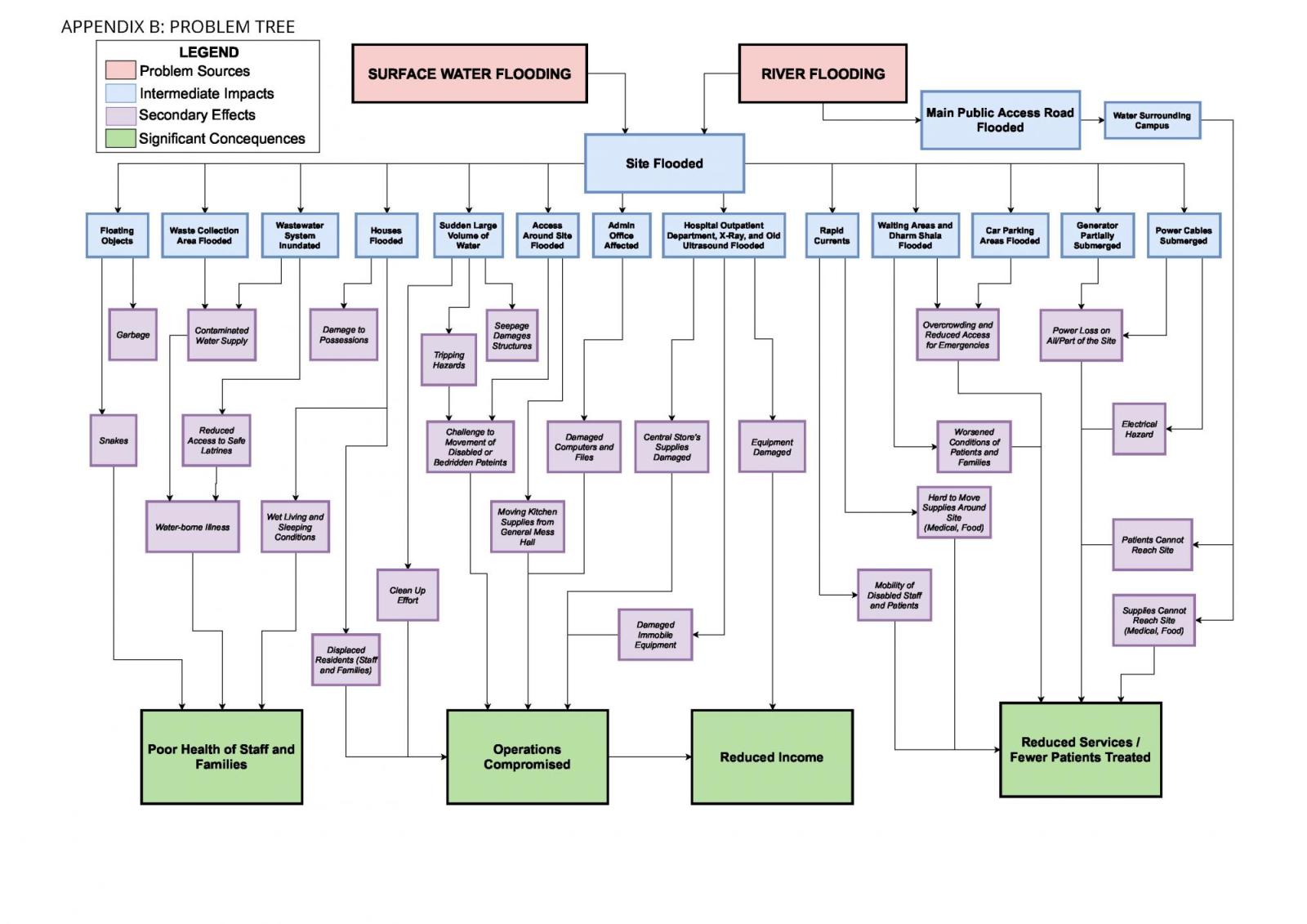

Drawing together these inputs for potentially complex flood mechanisms and the investigated impacts is crucial in order to properly define the problem before proposing solutions. The Problem Tree is a useful tool to draw to do this, showing the causal path between the problem source and the adverse outcomes.

In addition to the possible legal requirement, an FRA is an ethically critical first step before Flood Risk Management Solutions can be proposed. The FRA draws upon investigations into available historic data, theoretical modelling and community engagement. Once the full nature of the flood risk and adverse impacts are understood, the overall goal and purposes of possible interventions may be defined.

EMI may, in future, be required to engage beyond the local level; especially where the government does not have a strong evidence based flood risk strategy. In particular, this could be in relation to larger infrastructure projects: roads, airstrips or micro-hydro power. Additionally, EMI could engage more with strategic planning of refugee camps, or Flood Risk Reduction programs at a regional level.

In the meantime, EMI will continue to play its part to help produce sustainable and safe communities.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.