Considering interventions to avoid, substitute, control and mitigate flood risks

Monsoons in South Asia affect a large portion of the population every year, not only in terms of flooding of properties, but also the effect on critical infrastructure and livelihoods. It is in this context that EMI can bring extra value to our clients by providing a comprehensive Flood Risk Management Strategy.

In Development Design and Flood Risks, the concept of the Problem Tree was introduced. Now we must address the question of how the Problem Tree can be converted into a Solutions Tree. The proposed interventions may attempt to address the problem at various stages; anywhere between the source and the adverse outcomes.

It is common to think of dealing with the flood problem ‘head on’ through large infrastructure interventions such as flood defence walls around the property or raising the entire property above a defined flood level. The problem with relying on this approach alone is that the intervention tends to be cost prohibitive. Additionally, this fails to deal with the residual risk of extreme flood events. The preferred approach is more holistic: understanding the vulnerabilities and capacities within the community, and developing a sustainable strategy using available resources.

The Flood Risk Management Hierarchy

The Flood Risk Management Hierarchy (FRMH) is used by planners to inform an appropriate development strategy and land use allocation. The logic of the hierarchy begins first with understanding the problem through a comprehensive Flood Risk Assessment (FRA). Then following a similar model of risk management used in the construction industry, the interventions follow a sequence that first attempts to remove the risk (Avoid/Substitute), then control the risk, and finally mitigate the risk.

While the FRMH is primarily designed for land use planning, the logic was followed by EMI to generate a thorough strategy for Duncan Hospital in Bihar. Table 1 shows the interventions considered and how the principles of the FRMH were applied for this particular project.

Purpose |

Sub-Purposes |

Site-wide flood defenceStep 2: Avoid Note: Cannot Avoid by moving site, but potentially by preventing flooding reaching the site |

|

Strategic land use planningStep 3: Substitute |

|

Surface water management on-siteStep 4: Control |

|

Building-level protectionStep 5: Mitigate |

|

Preparedness / emergency planning and trainingAdditional Measures |

|

Avoid

In the context of planning new developments, the first step of the hierarchy after the FRA is to Avoid the Flooding. Where possible planned developments should avoid known flood risk areas. Governments and developers have the responsibility to apply thoughtful national and regional planning legislation. Planners have to weigh up the risks of flooding with the other planning objectives/drivers to determine the most sustainable land use allocation.

Of course, there are other pressures which lead land owners to develop in flood risk areas. The growing population and global urbanization continue to increase demand for new housing. Some communities only have land ownership in highly flood prone areas- such as on river floodplains, or in coastal areas subject to tidal flooding.

EMI’s clients frequently ask for assistance in the land selection process. This gives us opportunity to review and potentially avoid the flood risk through appropriate land selection. But how do we circumvent flooding risks when the project site is already fixed in a flood prone area? One option is to appeal to local authorities to commit to flood management infrastructure improvements. Additionally, engagement with stakeholders within the wider community may lead to a common understanding and a joint venture to address the flood problem.

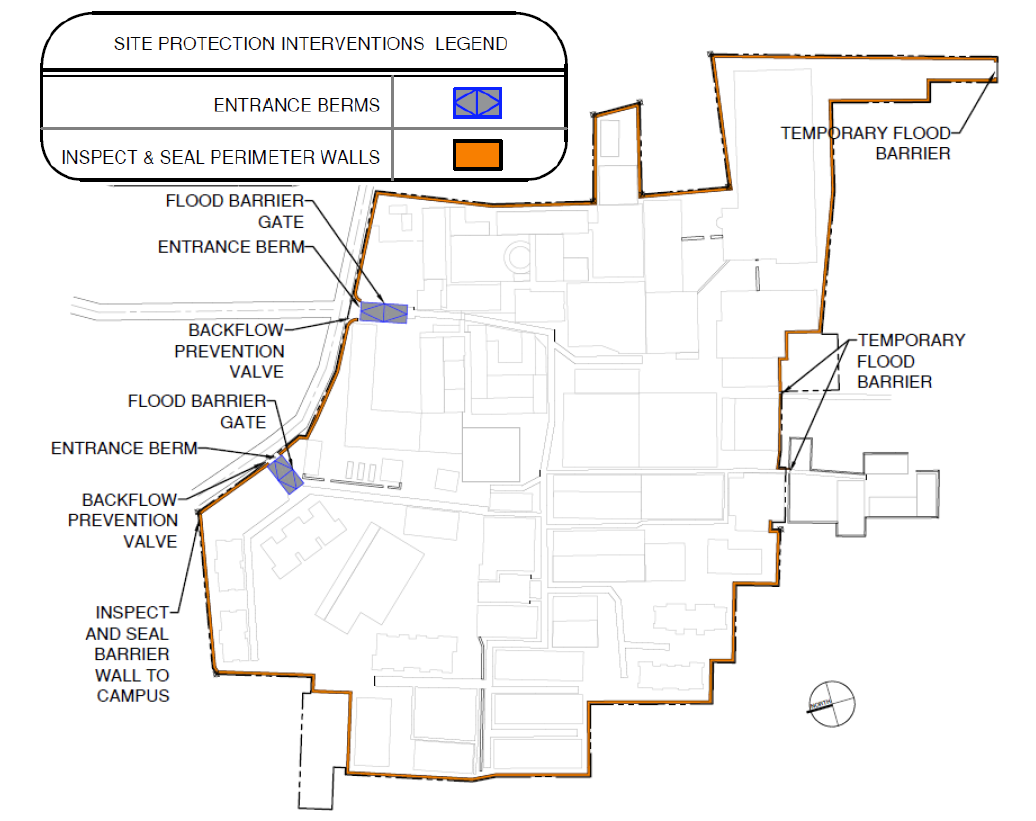

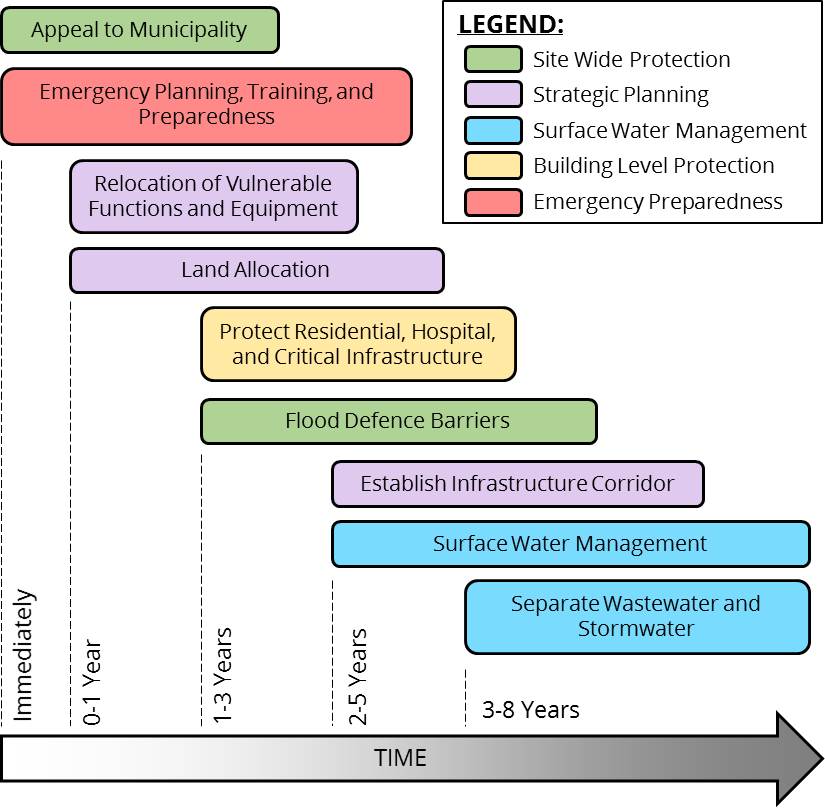

At Duncan Hospital, site wide flood defence measures were proposed to prevent a repeat of the devastating River flooding of 2017. Strictly applying the FRMH, flood barriers would fall under the Control category. However in this case EMI considered site wide flood defence as a way of avoiding the flood risk to properties within the site.

Substitute

The next level of interventions in the hierarchy involves considerations within the master-planning process, ensuring that flood risk to the most vulnerable assets is minimised. At a site level, this means substituting less vulnerable development types for those incompatible with the high degree of flood risk. For example, it may prove acceptable to locate a car park in a flood risk area that experiences minor flooding annually. However, critical infrastructure such as an electrical sub-station/transformer is a high value asset which must be placed in an area with minimal to no flood risk.

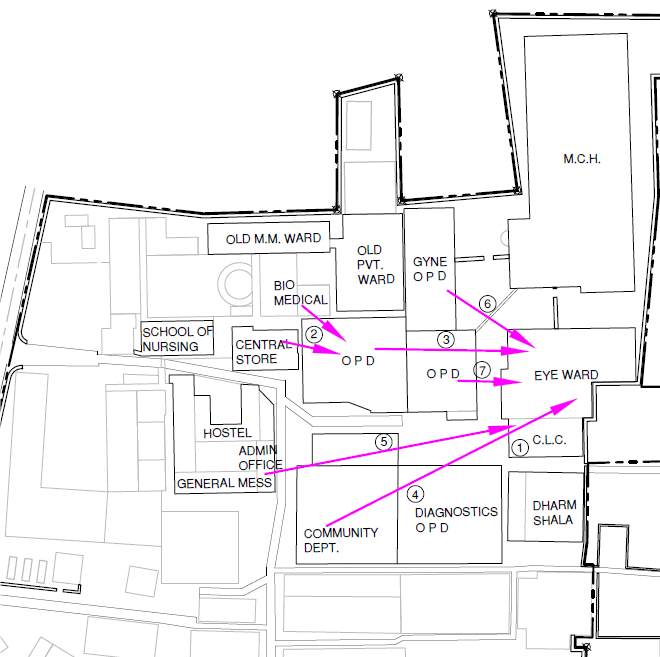

At Duncan Hospital, high value assets included X-Ray machines and the Central Medical Store, among others. EMI recommended a sequence for moving these assets to flood protected areas, that were either under-used or where less vulnerable functions could be shifted.

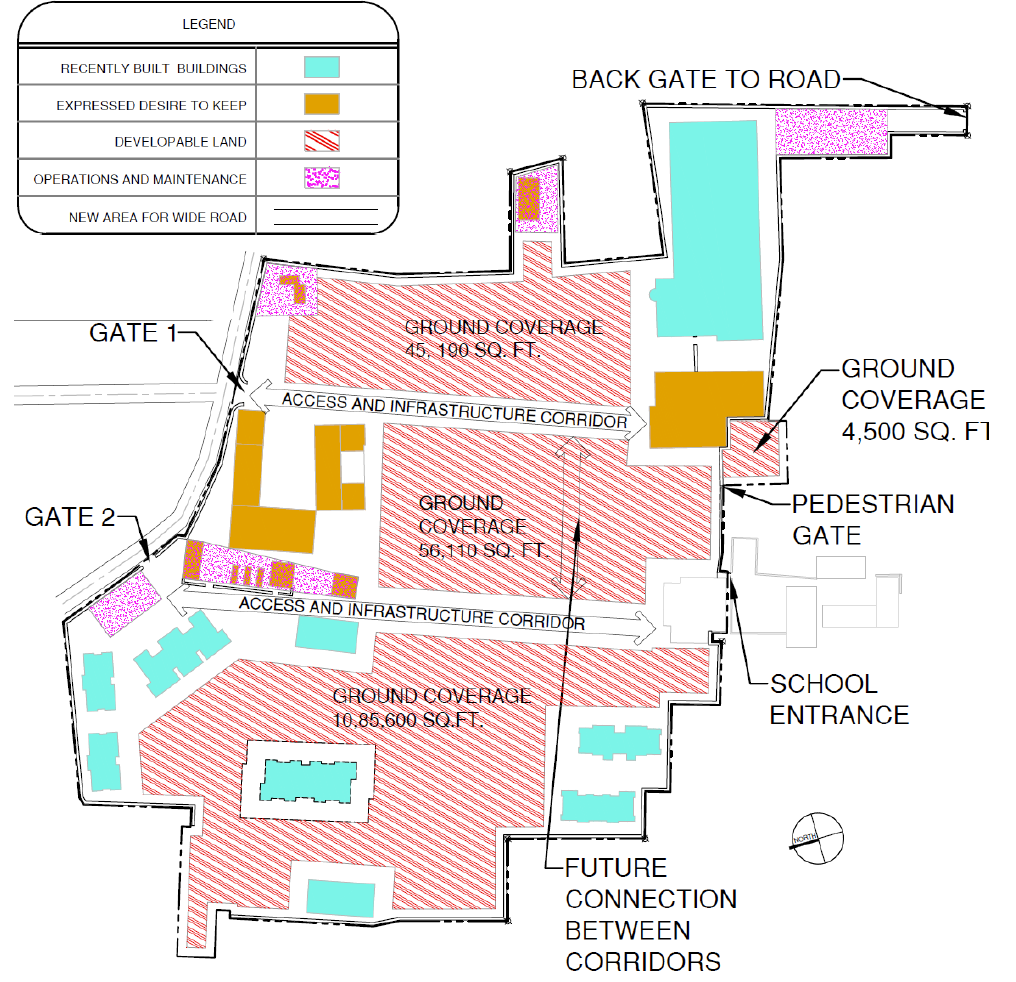

The Flood Risk Management Strategy dictated that the master-planning team consider critical land use areas. The allocation of developable land took account of the planned demolition of old buildings that were also vulnerable to flood risk. Areas that were used for critical infrastructure and maintenance were defined, and certain areas allocated for future critical needs. Infrastructure corridors were illustrated conceptually to highlight the importance of emergency and maintenance vehicle access around the site, as well as making provision for utilities, adequate drainage, flood routing and attenuation.

Control

At a national and regional level, flood defences and flood management schemes are implemented to control the frequency and magnitude of flooding. This may include shoreline protection, tidal defences, river basin management and surface water management plans.

Surface water flood risk may be controlled by a surface water management system, consisting of: collection, conveyance, attenuation storage, flow controls and outfall to the municipal or natural system. The main challenge at Duncan Hospital was the consistently high water level of the municipal drain, preventing discharge by gravity. Therefore, simply upgrading the existing site drainage capacity would have negligible impact. An attenuation tank and pump was recommended, to enable the discharge of surface water to the municipal drain. In the future Duncan Hospital must upgrade the drainage system to manage surface water flooding during extreme flood events. This can be completed in a phased manner along with new building developments on site.

Mitigate

The first steps: avoid, substitute and control, may not be adequate to deal with all flood risk. Also limited resources may prevent timely implementation of these interventions. The possibility of extreme events requires the acceptance of residual flood risk. Mitigation seeks to deal with these residual risks through flood resilient construction.

For Duncan Hospital, the Mitigation efforts are focused on modifications to the at-risk buildings and critical infrastructure. Recommendations were made to elevate footways, building floor levels, latrines and the waste collection area.

Emergency Procedures and Preparedness Measures

Beyond the five steps of the FRMH (Assess, Avoid, Substitute, Control and Mitigate), it is also important to consider Emergency Procedures and Preparedness Measures that tend less towards technical interventions and more towards training and equipping the community to increase their capacity to respond to flooding events. Such measures include early warning systems, contingency planning and provision of emergency items such as food and medical supplies.

While there is much overlap, nuanced differences exist between contingency plans and emergency plans. In flood management practise, contingency plans include building redundancy into systems to make it fail safe. For example, having a flood relief pump as well as a standby pump, or having a back-up generator that may be switched on in the event of mains supply failure. Rapidly deployable flood defence barriers or sand bag walls may be part of a contingency plan that attempts to prevent a foreseen flood emergency.

On the other-hand emergency plans provide a procedure for reacting to a present emergency. Evacuation plans, life boat rescue, water filter kit distribution, could all be part of a flood emergency plan. For all these, it is necessary to ensure that the at-risk community has sufficient training in the emergency procedures.

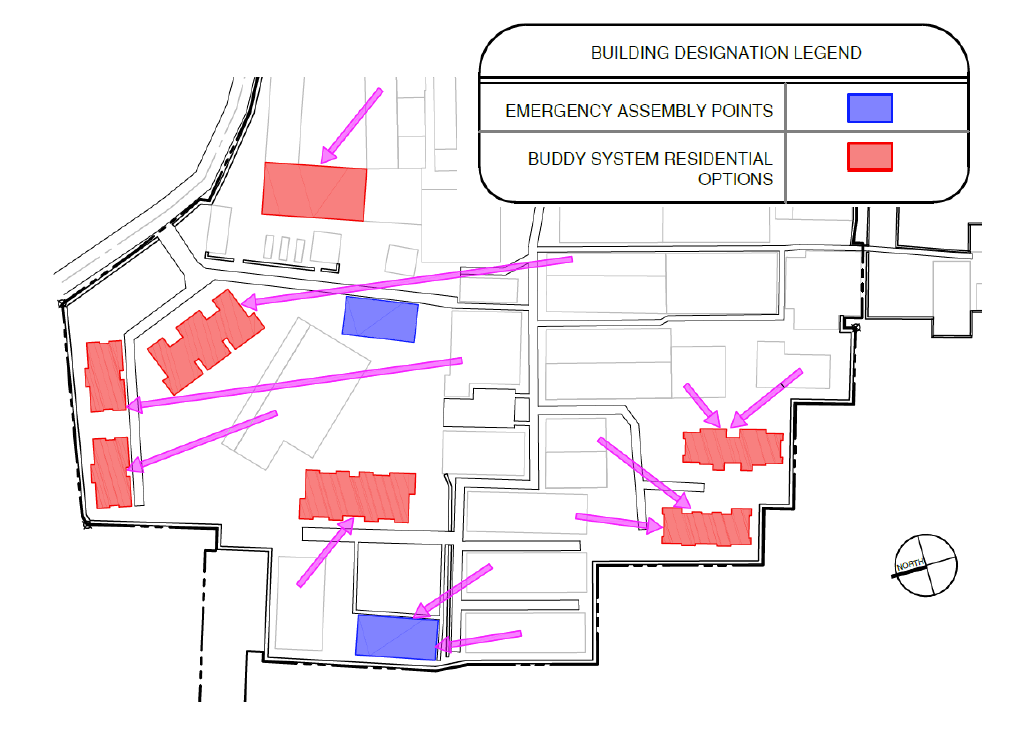

At Duncan Hospital, assembly points for storage of emergency provisions were identified, along with residential options for vulnerable families to stay during the flood event.

Conclusion

Upon completion of considering what efforts are possible, it is helpful to do a cost benefit analysis of the various interventions, costing asset loss, repairs and business closures. Damage to health and loss of life is more difficult to cost. Whether the exercise is qualitative or quantitative, it is nonetheless helpful in weighing up the interventions that are within budget and most cost effective.

For Duncan Hospital a pathway to flood resilience was recommended, that prioritized immediate actions that could be taken, along with future interventions in line with the client’s development strategy.

The causes and adverse outcomes of flooding are complex and wide ranging; thus the response must consider a range of interventions. The Flood Risk Management Hierarchy is one tool that can inform a comprehensive management strategy. Within this hierarchy we see the need for multi-disciplinary participation including regional and urban planning, site master-planning, landscape design and architecture, as well as community engagement and an understanding of wider environmental factors. EMI can pull together these disciplines and, in partnership with our clients and their populations, help create more resilient communities.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.