How can an EMI architecture best serve communities and the church?

The answer might seem elusive, but most would fundamentally agree that to provide a service of any value you must first know and understand the needs of those being served. In the corporate world this can be partly achieved through impersonal activities like behavioral data collection and analytics. More specifically, it is achieved in the practice of architecture through the programmatic requirements initially provided by the client. But to design spaces that help transform communities implies a deeper level of understanding—one that can only be achieved through enduring relationships of trust. To serve communities and the church in this way is to enter into community with them. To both know them and be known by them, and to actively participate in their transformation.

To explore the various stages of trust-building in community over time, we can evaluate EMI’s architectural approach for a multi-phase project in Uganda with The Amazima School. This project began in early 2014 and has continued over the last five years. EMI’s initial involvement was launched with a traditional volunteer team, but has since involved a much broader group of local, in-house, and remote designers. And not only designers, but construction managers and workers, educators, staff, students, and other community members were involved as well. All of these participants have served as co-creators to inform the evolving design of future project phases. They have helped move the baseline of an EMI architecture towards more sustainable, affordable, and transformational solutions.

Stage One: Entering and Engaging a Community

We seek a complimentary diversity in the makeup of our teams and we enlist cultural brokers to help us understand the people and places we serve. However, regardless of any previous research, experience, or local knowledge, to enter a new community is always to enter an unknown environment. We must prepare to build trust with a unique group of people with unique stories, struggles, hopes, and dreams in the context of a unique project site. This requires we first identify ourselves accurately as outsiders and guests and take the posture of learners and observers.

Not only do we enter a new community as outsiders, but also as individuals with some degree of self-focused identities and behaviors. In most scenarios, we are building new relationships of trust within the EMI team as well as with our partners and the communities they serve. Making the transition from individual to shared identities within each of these groups happens naturally in an environment of story-telling. Sharing our struggles and stories helps us be known and trusted, especially as we relate our stories with God’s overarching and unifying gospel narrative. As we actively encourage those around us to share their own stories, we move from observation into participatory learning and action.

With a basic level of trust established, our stories begin to merge. A new design community encompassing the project’s current stakeholders begins to form, drawing from the diverse backgrounds, skills, and experience of its members. It is interwoven around a newly shared identity and vision. The task of this community is to explore the design of classrooms, assembly space, student and staff housing, and campus-wide ancillary spaces for The Amazima School.

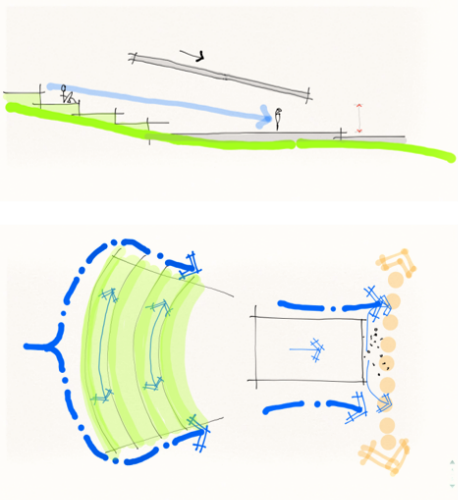

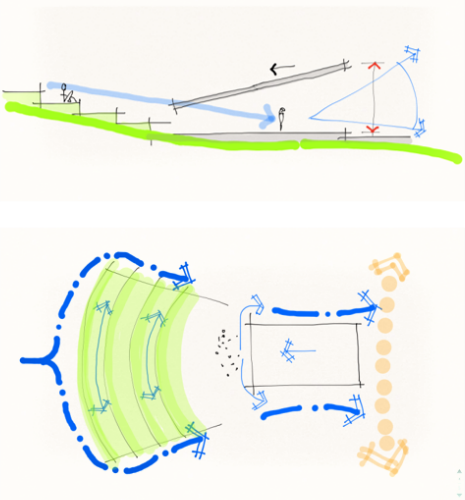

For the school’s main assembly and dining space (later referred to as the chapel) a unique storyline begins to emerge. It is shaped by the community’s combined input: The ministry founder speaks of an inviting, humble architecture—one that integrates a familiar material palette from a rural Ugandan context and connects to the surrounding landscape to form a place of peace and tranquility. The civil engineers express pragmatic concerns about the placement of the structure relative to site patterns of storm-water drainage. The future Head of School envisions a rock of stability breaking the current of brokenness within the vulnerable populations the school serves: Jesus is the rock. Through His grace, the water’s destructive force is transformed into a sheltered pool for learning, healing, and restoration.

Roof pitched along slope:

- clear views to stage

- no civic identity

- watershed on to path

Roof pitched against slope:

- obstructed views to stage

- civic identity

- watershed on to amphitheater

Two inwardly sloped roofs:

- clear views to stage

- civic identity

- watershed onto water channel

In the initial design stages, it is the role of the architect working in community to synthesize this diverse input into cohesive foundational concepts. Avoiding the pursuit of independently developed, isolated solutions is essential. The object is to maintain a creative environment where multiple ideas can be quickly and collaboratively explored, and then communally accepted or discarded. Seed planting in community is thus the primary role of the concept team, both in establishing relationships of trust and in seeding the basic building blocks of the design.

Stage Two: Learning and Growing Together in a Community

Design development following the initial concept work may proceed along many different paths and timelines. However, an EMI architecture that serves communities and the church will continue to nurture relationships of trust. In the case of the Amazima School, close proximity to EMI Uganda has provided additional opportunities. These have included shared life experiences among staff, honest discourse around on-going project challenges, and joint engagements in surrounding communities, including the local church.

These deepening connections continue to inform the developing Amazima architecture. On-going listening, learning, and interaction bring an increased understanding of and confidence in each member’s contributions. They bring increasing effectiveness to each successive stage of the design effort. The result is a design in closer alignment with current and future needs.

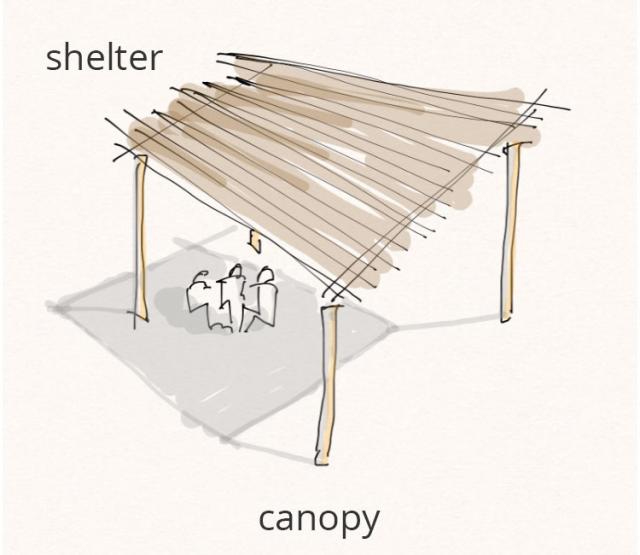

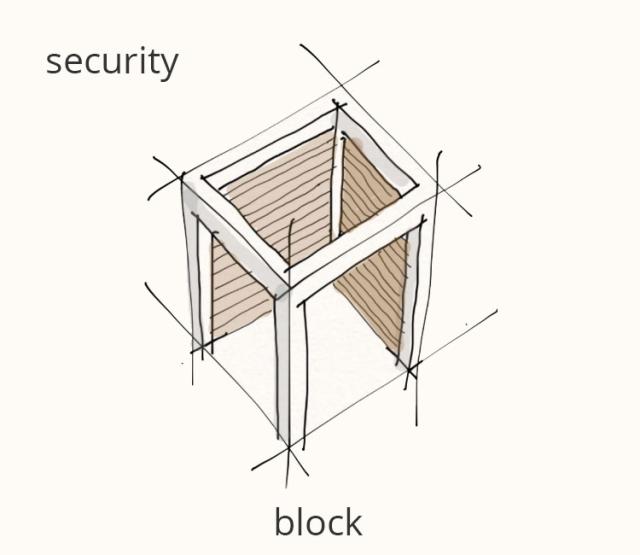

Delayed until Phase 2 in 2017, the chapel was refined in detailed design with further acoustical studies and a revised stage layout for more flexible performance options. In construction, the gradient of the natural amphitheater behind the structure was decreased. This was a response to local climate conditions and cultural traditions. Community celebrations typically attract large crowds and as a result, there is always a need to accommodate temporary, tent structures. These make room for the celebrants and shade them from intense sun during special events. While these growing relationships allowed for an adaptable and evolving design, their consistency also ensured key original concepts remained central.

This developing architecture also brings opportunities for relationships of professional and spiritual discipleship within an ever-broadening community. Over five years of partnership with the Amazima School, EMI design and construction management teams have interacted with local architecture students in regular site visits, along with other experienced local professionals. Fundamental decisions carried forward from the concept design have ensured the involvement of local craftsmen in every phase of construction. These craftsmen have benefitted by learning and growing in their trade through innovative adaptations of local methods. Beyond this, there have been on-going opportunities for the gospel to transform their personal lives, families, and communities.

Stage Three: Leaving a Community

Exiting communities well is also dependent on relationships of trust. For an initial EMI team, this often means allowing other architects and designers to enter into the developing design. Those involved in later stages must also consider the project’s eventual transfer to the partner ministry and ultimately to the community at large. The depth and quality of our relationships will have a lasting impact in the communities we serve—far more impact than the buildings we design and construct. Our own stories also change with each experience, impacting our future work in other communities. Thus the story continues…

EMI’s early-concept design work is only the first step in a project that may take many years to complete. However, it sets the tone for all future design and implementation stages. The developing design is informed by on-going community interaction, the diversity of its participants, and the discipleship relationships that are a part of the design process. An EMI architecture is one that only matures over time in the richness of community, and it will never stop maturing until God’s work of restoration is fully complete.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.