The Intersection of Convention and Innovation

In good design, ‘intersection’ is the point where design factors, deemed important for the process, come together to establish a unified, cohesive, and pleasing whole. At EMI, we refer to this as ‘appropriate design’. It is a term used as both a design reminder as well as a design approach. Used either way, it expresses the primary challenge for EMI design; it often takes place where conventional construction methodology, sometimes expressed in deep-seated vernacular design, meets innovative ideas.

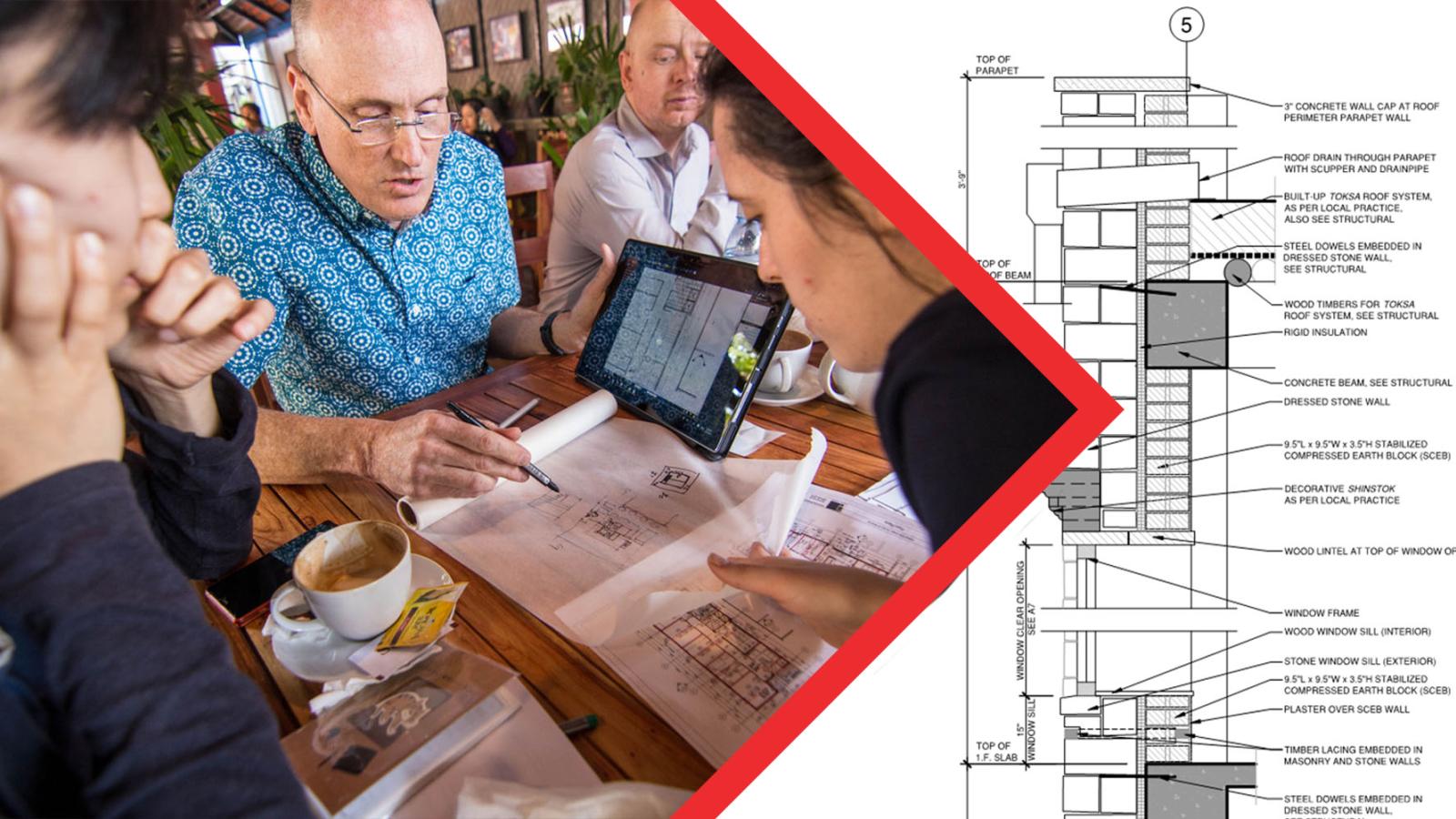

Whether architects involved with EMI are traveling by ground transport to another part of their own country or they are flying by air to another part of the globe, they are often designing in an unfamiliar context. In this position, their initial challenge is to identify and understand unfamiliar factors which will impact their design.

This article explores five design factors which will assist architects involved with EMI, who are designing away from a familiar context, to develop an appropriate design, one that rests comfortably at the intersection of convention and innovation.

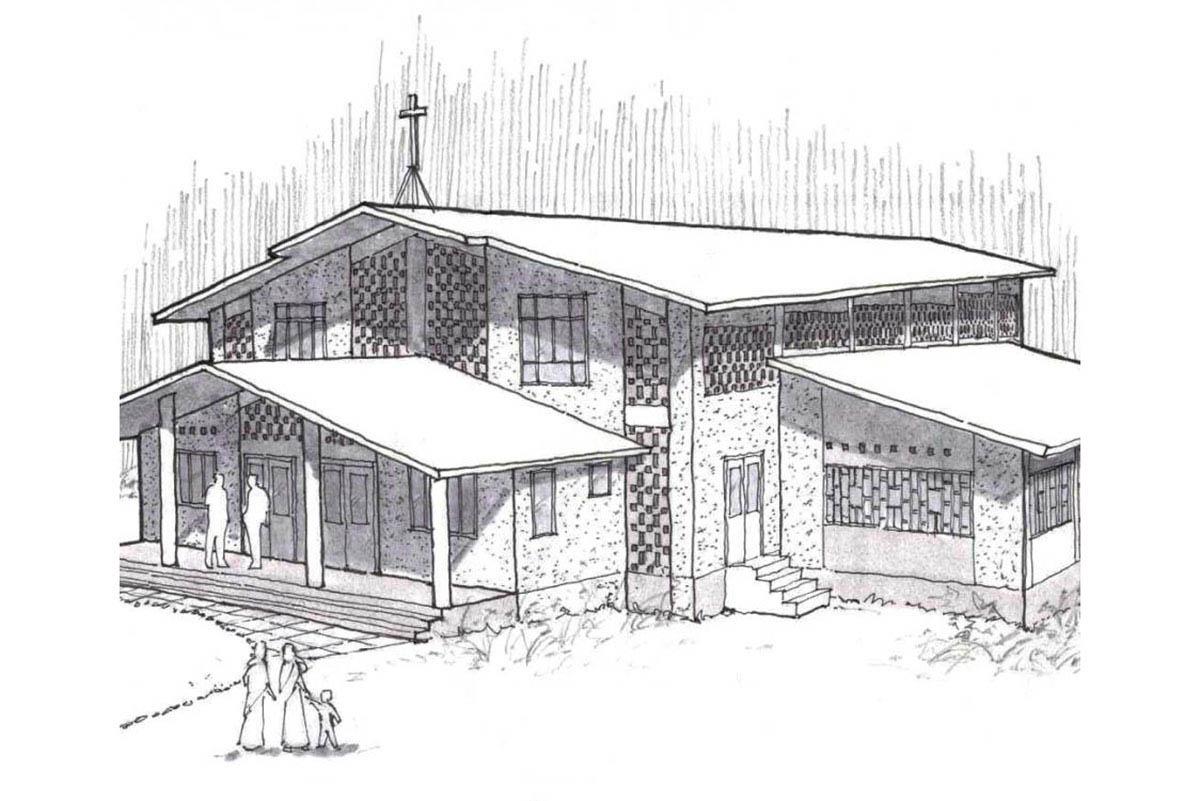

Establishing an appropriate design approach is key to EMI design. When an architect designs the ‘right’ building for their client it will support intended activities with a sense of ease and purpose. It will also embody as well as reflect their character and values. A great challenge for EMI architects in determining an appropriate design approach is that most ministry clients will be unable to articulate this for themselves. This is because the project they have brought to EMI is the largest, and typically most public, capital project they have ever undertaken so determining and conveying suitable design elements to their architect can be challenging, much like a student deciding what to wear at their graduation.

Is the design too extravagant? Does it lack vision? Should the design be more ‘contemporary’ or should be more traditional in style to respect the local culture?

EMI architecture, through open communication and honest dialog, seeks a balanced design; an appropriate design approach which is not too extravagant, reflects a vision for the future, and is neither too alien nor overly captured by tradition.

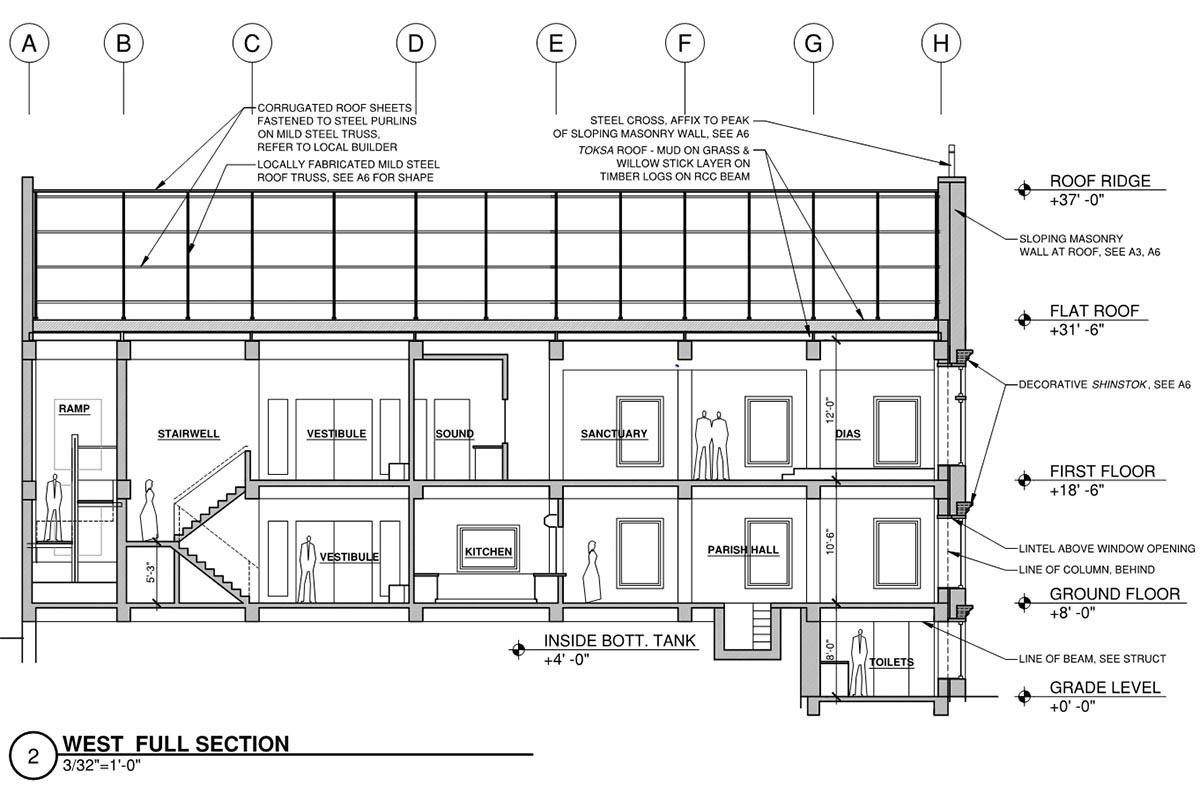

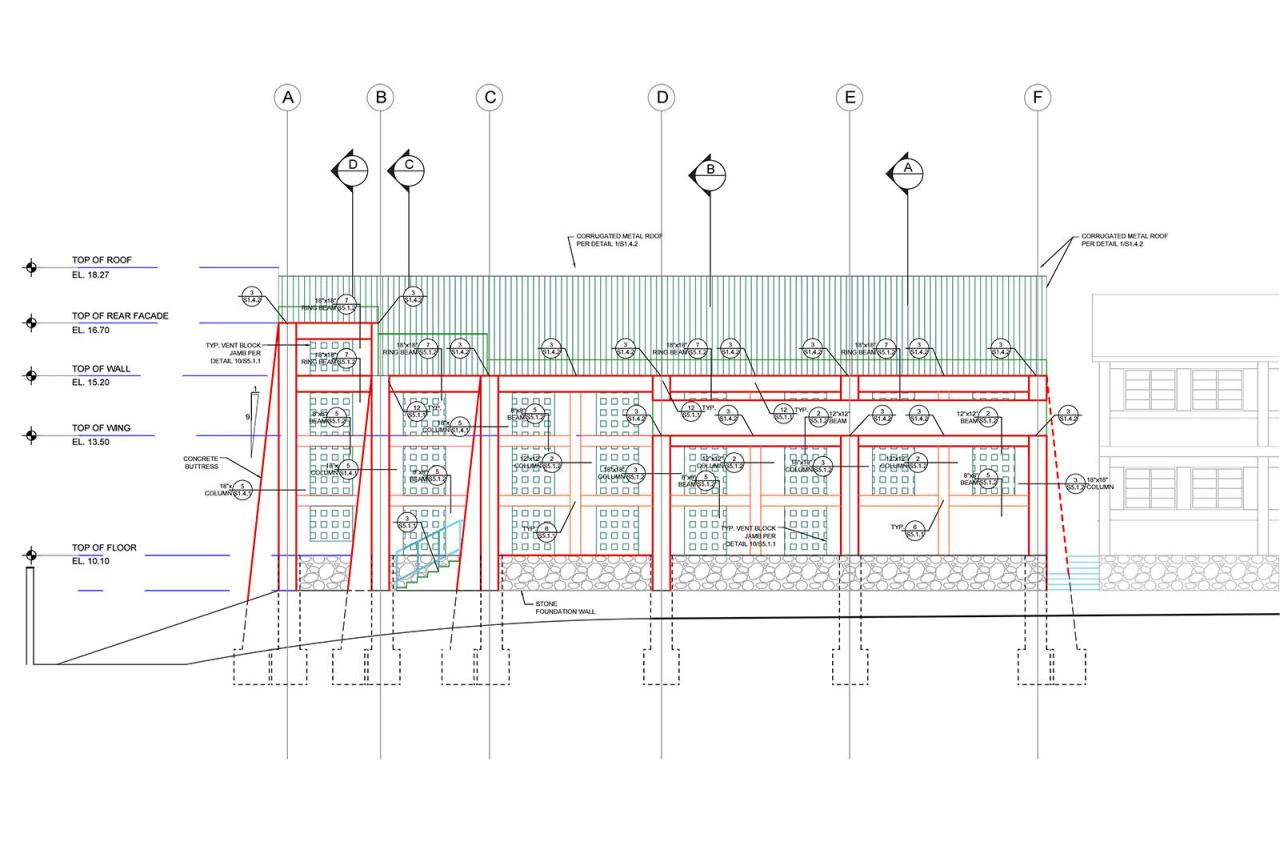

Incorporating local construction systems is key to EMI design. Typically, EMI architecture incorporates some mix of or all local construction methods, materials, and labour. In Haiti, for example, confined masonry construction is common practice but no matter how its executed, this construction method would never meet North American code because of its seismic conditions. However, without imposing unfamiliar construction systems, methods, or materials, design guidelines resulting from post-quake observation and research, which address site, construction, and structural considerations, can enable architects to create stronger buildings than what is typical.

This form of innovation, which includes the placement of openings as well as reinforced walls to buttress exterior columns, is hidden within what appear to be conventional walls. Regardless of architectural expression this integrative approach is both pragmatic and effective.

Affordable and manageable building maintenance is key to EMI design. With long-term viability and sustainability being important values in EMI architecture, understanding and accounting for affordable and manageable building maintenance is paramount in the design stage. While innovative environmental control systems garner lots of attention, each system, whether passive or active, that addresses lighting, air movement and/or conditioning, water supply, sanitation, power, privacy, and security, must be evaluated beyond initial performance and also account for the end user’s ability to maintain building functionality throughout the life expectancy of the facility.

Maintenance and repair must be affordable, serviceable in-house or by a community contractor, and replacement parts must be available locally. Technical aspects of the design should be accompanied by lifecycle planning for implementation, phasing, maintenance, replacement, and even decommissioning.

This important part of EMI design constitutes proactive due diligence. Beyond the immediacy of initial risk (cost) and reward (building performance), careful consideration of ongoing maintenance recognizes and addresses both the short and long term economics of a facility for our ministry client.

Pushing the envelope for “better” is key to EMI design. While a majority of ministry clients understandably gravitate toward familiar, economical solutions, EMI is often uniquely positioned to introduce ‘better’ solutions. While some design approaches and even innovative design can be hidden within conventional design and construction methods, some newer design approaches, when introduced and integrated appropriately, can have a profoundly positive impact on a project while remaining within economic considerations.

An example of this is the use of two separate roof systems to create cooler and quieter interiors, in hot climates and during rainstorm events respectively. This is a ‘sandwich’ system involving an upper roof to physically block sun, rain, and to rebuff wind, while a lower roof acts as a ceiling for the interior to keep it clean and performs as a sound barrier. In-between is a gap where air flows to carry away heat radiating down from the upper roof. While some systems for this principle can be quite complex, expressive, and therefore expensive, the concept of the ‘double-roof’ is not complicated and can be executed using modest means to improve a building’s indoor experience.

A second example is solar-powered lighting. While appropriately captured, regulated, and distributed natural light within a building is an ideal, it can be a challenge when applied to simple construction methodologies. If an important goal is simply to provide a few hours of lighting, such as enabling students to study 2-3 hours each evening, solar solutions utilizing increasingly inexpensive solar panels and small, locally available batteries have become more and more economical and is an innovative, yet economical use of new technology.

Embracing innovative design approaches, which marry programming and building design, spotlight a ministry’s values and invite as well as encourage creativity in EMI architecture.

Considering fundraising is a key to EMI design. Sometimes a ministry client prefers a specific design approach because it might produce a facility that’s more attractive to potential funders. If this design is less ‘convention’ and more ‘innovative’, this design may be received positively in the community as ‘forward-thinking’, however, it may also alienate some in the local community. Ultimately, this balance must be discerned by the ministry client.

Finding the appropriate intersection of convention and innovation arose recently on a project for a new medical clinic in Haiti. It would replace a very modest, 60-year-old facility. As the ministry will be raising funds for its construction in North America, the ministry was excited with the innovative design toward managing the region’s harsh climatic conditions. However, they recognized that while pragmatic, the design might come at a high cost. The solution was to deliver the proposal as-is to a local contractor for pricing but to also be prepared to find a less expensive design alternative if the anticipated budget is exceeded.

This balance of pragmatism and vision is needed in EMI’s setting where most clients are ministries operating in a non-profit, charitable environment and funding for capital projects is rarely in-place up-front. Keeping this reality in mind, we come to a final key to EMI design.

Designing without an ego is key to EMI design. At EMI, searching for the intersection of convention and innovation is a faith exercise. It is one of listening and then obeying, and must be done without ego. As in the life of a believer who seeks to develop maturity in character, this is the path toward an appropriate design to establish a unified, cohesive, and pleasing whole.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.