What should an EMI Architecture stand for?

EMI's four-stage process for electrical engineering projects. Learning from the forensic diagnosis of distressed CEB buildings in West Africa. Beyond septic tanks. These are some of the 'normal' subjects for EMI Tech, so you can imagine our apprehension when we were asked to write 'Towards an EMI Architecture.' Those four words are enough to conjure up memories of famous manifestos from the likes of Le Corbusier in the mid-twentieth century. Before we can even begin to address the technical aspects of an EMI Architecture, we need to ask what an EMI Architecture should look like. What should we stand for? What should we aspire to?

Born in 1982, EMI has just turned 35. Over these years, the world of architecture has changed dramatically. We have seen sweeping changes socially, economically, and environmentally and we have seen dramatic advances in technology and construction. Around the world more buildings than ever are sustainable, affordable, and transformational. What, then, makes EMI different? What makes us unique?

To us, the answer lies not in our architectural work of plans, details, and renderings, but rather in our architectural approach. EMI is a global organisation with a local perspective, working on projects all over the world. On each project, we strive to work within the local context to design and construct culturally-appropriate facilities. We do this because we believe that architecture is at its best when we, as architects, think beyond simply buildings and embrace the people and the stories that we find there. We are passionate about an architecture that is coloured by its surroundings: An architecture that tells people's stories and gives voice to their vision. It is the architecture of community, and it is about bringing people into relationship and seeing people restored by God.

What is an EMI Architecture? It cannot simply be a general term to describe buildings and structures. An EMI Architecture is not defined by an aesthetic or a style, nor is it likely to be found on the glossy cover of architectural magazines. Much of what architects do is about promoting ourselves and our knowledge over others. Yet an EMI Architecture is about exactly the opposite. It is about knowing that we do not know everything, it is about looking around for help and listening to others. An EMI Architecture is about collaboration and participatory design because we believe that the solutions we imagine together are stronger than what we could each achieve apart. As Roger Duarte (a local architect working at EMI Nicaragua) put it, "The architectural product of EMI is not simply a building, it is a way of thinking together."

An EMI Architecture, then, is about moving from the "specificity of the problem to the ambiguity of the question." It is about asking, 'What does architecture look like if we stop speaking and start listening?' 'What does it look like if we approach a new project, a new place, or a new people, and think not about what we can do, but instead ask questions about our profession and our practice?' 'How do we work with integrity and invest in those around us?' An EMI Architecture seeks to truly understand our ministry partners and the people we are serving. It listens to local expertise, understands local materials and construction practices, and invests in local design professionals so that we can realise culturally-appropriate buildings that are sustainable, affordable and transformational.

In Mexico, for example, inexpensive labour is readily available and this has a considerable impact on the choice of building materials and construction systems. As a result, the majority of buildings in the country still use masonry construction. Although it is labour-intensive and time-consuming, in Mexico - like most Central American countries - masonry construction is widely used. An architectural project there will almost certainly have some concept or stage that requires cement, sand, and gravel, and some type of block or brick. This is quite a contrast to most European or North American contexts, where labour-intensive masonry construction is increasingly avoided for environmental reasons or due to concerns over time and cost control. The result is that designers becoming less and less familiar with masonry construction, and more and more familiar with technical cladding systems using glass and steel.

If we, and the organisations we partner with, really want to impact the places where an EMI designed project will be built, we must take these differences seriously. We must recognise that those who come from outside the local context may not have a good understanding of the design and construction choices required locally and the impact they have. We must understand that the people who benefit from an EMI-designed project are not only the users of the buildings, but the wider community that surrounds it: the bricklayer, the contractor, the architect, and the engineer. These people, who have knowledge and expertise in their field, are key to realising culturally-appropriate buildings that are sustainable, affordable and transformational.

If the goal of an EMI Architecture is to construct buildings that fit the communities they serve, then surely the best way to achieve this is to have as many local hands involved as possible. Around the world, ministries are finding new ways to engage people in the communities that they serve. As EMI has seen with our established construction management programme in Uganda, and the much newer one in Nicaragua, job opportunities can directly impact the physical needs of a community, build relationships, and develop people through discipleship.

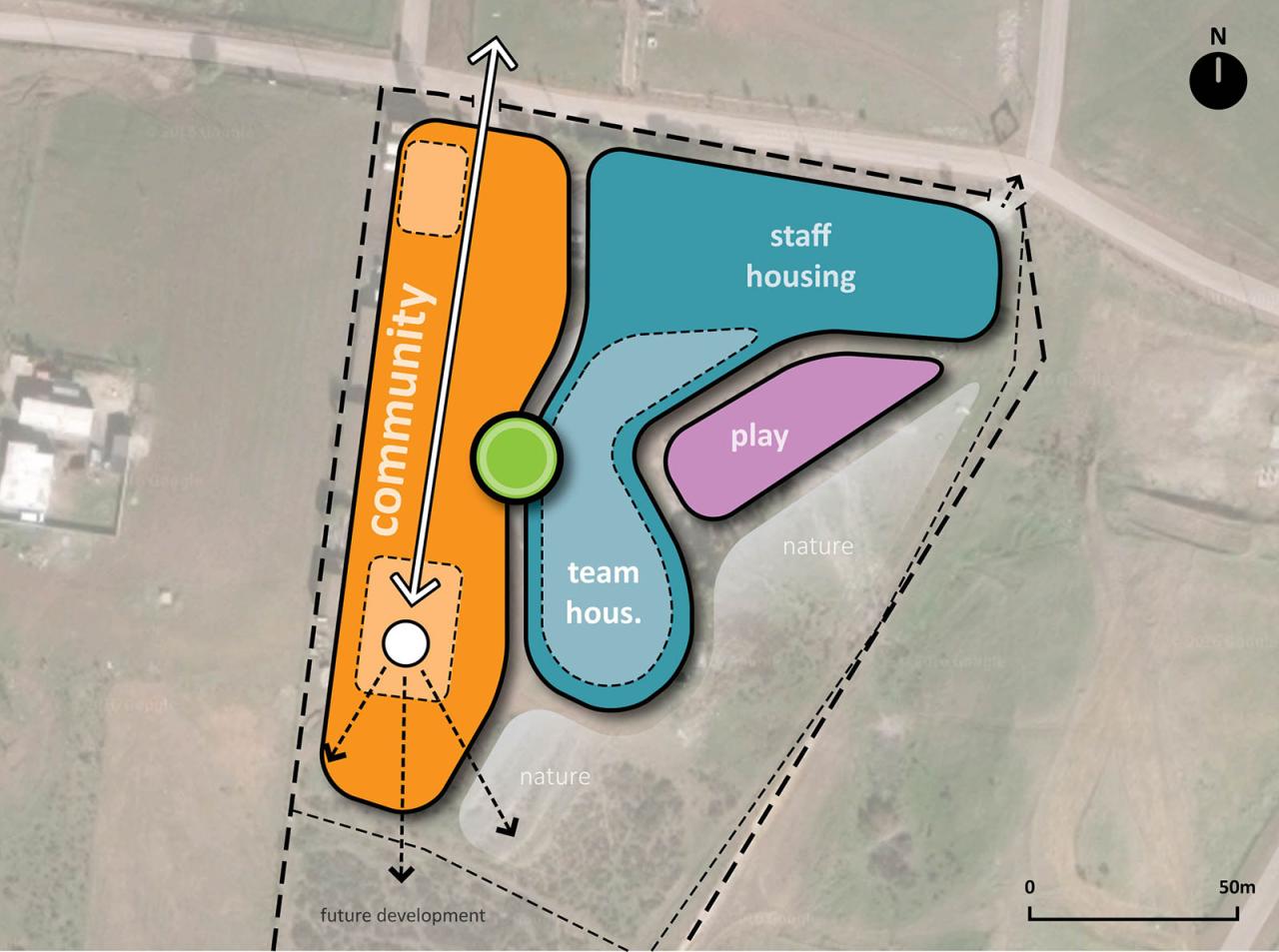

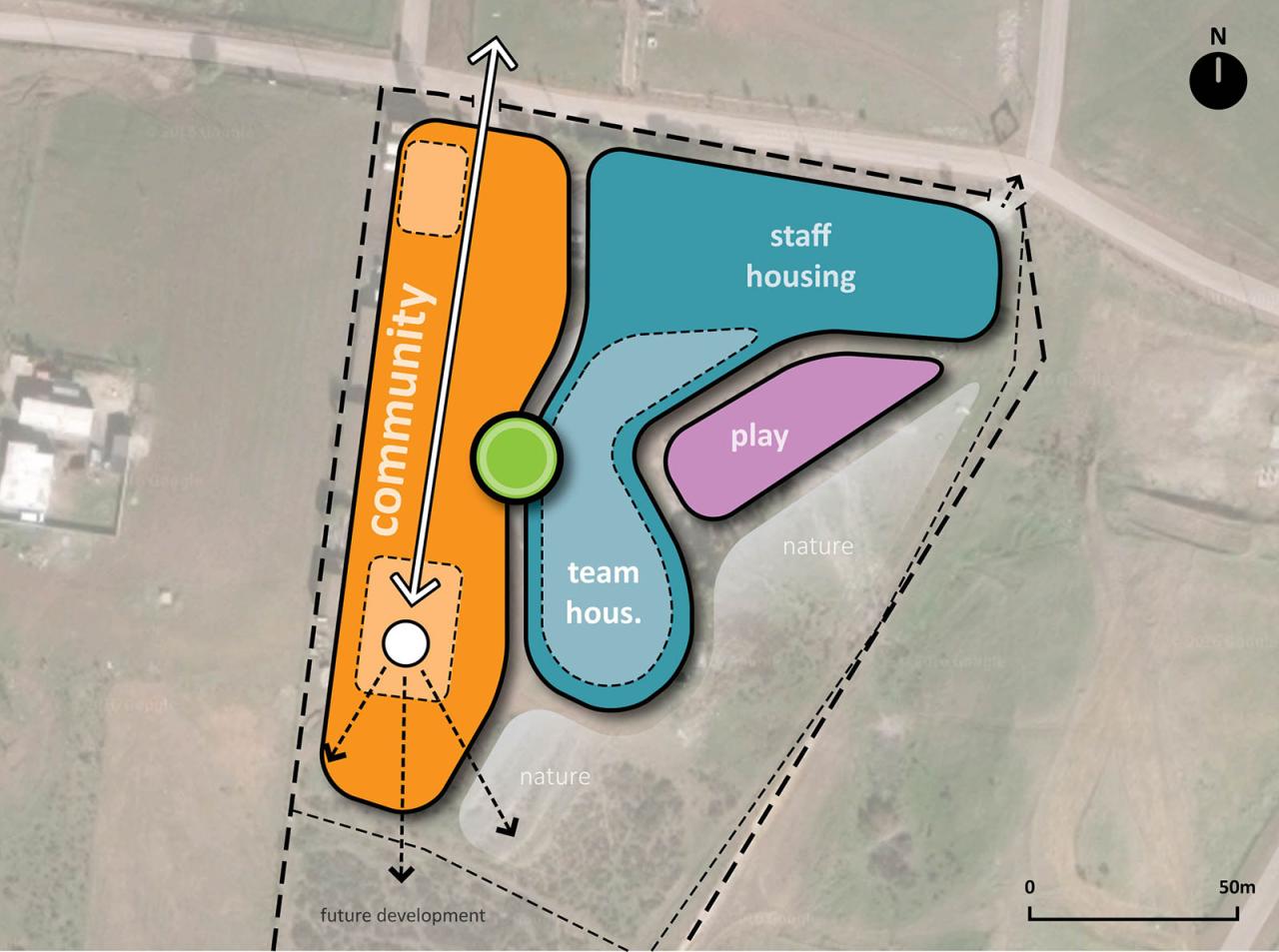

An EMI Architecture, then, must work with local design professionals. They are incredibly valuable because they can answer a multitude of questions as only a local can - and even if they do not know the answer, they know where to find it. We work globally but we think locally. The projects designed by EMI for YUGO Ministries in Mexico are clear examples of this. Each year YUGO hosts thousands of short-term missionaries from North America and Mexico at their Outreach Centres in Baja California. New facilities were designed for each centre, with dormitory accommodation, offices, meeting and worship areas, and spaces for community outreach. The construction systems used included reinforced concrete foundations, load-bearing confined masonry walls, and timber framing for internal walls, while upper floors used concrete joists and polystyrene blocks, a common local system. The buildings were designed to be in keeping with the look of local architecture, blending colours, materials, and traditional forms.

It would be easy, then, to think that this is an example of an EMI Architecture. However, what was unique in this and other EMI projects was not the construction method nor the materials used, but the way in which design was approached. Both EMI, in design, and YUGO, in construction, involved local architects and engineers in the project from the very beginning, with the aim of not just building buildings, but building people. The project built relationships and community among volunteers, design professionals, contractors, and local labourers. This interdisciplinary and cross-cultural team was all about collaboration: Working together, listening to each other, and learning together. This approach towards an EMI Architecture goes beyond our designs, our drawings, and our details.

Hacia a una arquitectura de EMI

¿Qué debería representar la arquitectura de EMI?

"El proceso de cuatro etapas de EMI para proyectos de ingeniería eléctrica", "Aprendiendo del diagnóstico forense de edificios de bloques de tierra comprimida dañados en África Occidental", "Más allá de tanques sépticos", son algunos de los temas "normales" que se pueden encontrar en EMI Tech, así que podrán imaginar nuestra aprensión cuando nos pidieron que escribiéramos acerca de: "Hacia una arquitectura de EMI", tan sólo estas palabras son suficientes para evocar en nuestra mente recuerdos de manifiestos famosos de gente como Le Corbusier a mediados del siglo XX. Antes de que podamos comenzar a abordar los aspectos técnicos de una arquitectura de EMI, debemos preguntarnos ¿cómo debería ser una arquitectura de EMI?, ¿Qué deberíamos representar?, ¿A qué deberíamos aspirar?

Nacido en 1982, EMI acaba de cumplir 35 años y es de notarse que a lo largo de estos años el mundo de la arquitectura ha cambiado drásticamente; hemos visto profundos cambios en lo social, económico y ambiental, así como avances dramáticos en tecnología y construcción. Hoy más que nunca, los edificios alrededor del mundo son sostenibles, asequibles, transformables y transformadores; Entonces, ¿qué es lo que hace a EMI diferente? ¿Qué nos hace únicos?

Para nosotros, la respuesta no radica en el trabajo que se realiza en los planos arquitectónicos, o en los detalles, o en los renders; la respuesta radica en nuestro enfoque arquitectónico. EMI es una organización global con una perspectiva local, que trabaja en proyectos en todo el mundo; en cada proyecto, nos esforzamos por trabajar dentro del contexto local para diseñar y construir instalaciones que sean culturalmente apropiadas. Hacemos esto porque creemos que la arquitectura no puede ser mejor que cuando, como arquitectos, pensamos más allá que sólo edificios y abrazamos a las personas y las historias que allí se encuentran. Nos apasiona una arquitectura coloreada por su entorno: una arquitectura que cuente las historias de las personas y que le de voz a su visión; se trata de la arquitectura de la comunidad, se trata de crear relaciones entre las personas y de verlas siendo restauradas por Dios.

¿Qué es una arquitectura de EMI? No puede ser simplemente un término que describe de manera general edificios y estructuras; una arquitectura de EMI no está definida por la estética o por un estilo, tampoco es probable encontrarla en las portadas lustrosas de las revistas de arquitectura. Gran parte de lo que los arquitectos hacen es promoverse a sí mismos y su conocimiento sobre los demás; sin embargo, una arquitectura de EMI es exactamente lo opuesto. Se trata de reconocer que no lo sabemos todo, de buscar ayuda y escuchar a los demás; una arquitectura de EMI se trata de colaboración y diseño participativo. Esto, porque creemos que las soluciones que imaginamos juntos son más fuertes que las que pudiéramos lograr por separado. Como dijo Roger Duarte (arquitecto local de la oficina EMI Nicaragua), "El producto arquitectónico de EMI no es solo un edificio, es una mentalidad."

Una arquitectura de EMI, entonces, se trata de salir de "la especificidad del problema a la inespecificidad de la pregunta", se trata de preguntar: "¿Cómo luciría la arquitectura si dejáramos de hablar y comenzáramos a escuchar?". "Cómo sería, si al abordar un nuevo proyecto, un nuevo lugar o a nuevas personas no pensáramos en lo que podemos hacer, sino que en lugar de eso hiciéramos preguntas acerca de nuestra profesión y práctica". "¿Cómo podemos trabajar con integridad e invertir en aquellos que nos rodean?" Una arquitectura de EMI busca entender verdaderamente tanto a nuestros compañeros de ministerio como a las personas a las que servimos; busca escuchar la experiencia local, entender los materiales locales y las prácticas de construcción, así como invertir en profesionales de diseño locales, para así, poder realizar construcciones culturalmente apropiadas que sean sostenibles, asequibles y transformacionales.

En México, por ejemplo, se ha vuelto fácil obtener mano de obra barata, esto influye considerablemente en la elección de los materiales y sistemas de construcción. Como resultado, la mayoría de los edificios en el país todavía utilizan la mampostería como método de construcción a pesar de que requiere mucha mano de obra y consume mucho tiempo (en México, como en la mayoría de los países centroamericanos, la mampostería es ampliamente utilizada como sistema constructivo). Un proyecto arquitectónico en alguno de estos países seguramente tendrá algún concepto o etapa que requiera cemento, arena y grava, y algún tipo de bloque o ladrillo; esto, en contraste con la mayoría de los contextos europeos o norteamericanos, donde la construcción de mampostería con uso intensivo de mano de obra se evita cada vez más, ya sea por razones ambientales o debido a preocupaciones sobre el rendimiento tiempo-costo. El resultado de esto es que los diseñadores están cada vez menos familiarizados con la mamposteria y más familiarizados con sistemas de revestimiento técnico que utilizan vidrio y acero.

Si nosotros, y las organizaciones con las que nos asociamos, realmente queremos impactar los lugares donde habrá un proyecto diseñado por EMI debemos tomar en serio estas diferencias; debemos reconocer que aquellos que vienen del exterior y no pertenecen al contexto local pueden no entender bien las condicionantes locales del diseño para la construcción, así como el impacto que estas tienen. Debemos entender que las personas que se benefician de un proyecto diseñado por EMI no son solamente los usuarios de los edificios, sino también la comunidad que lo rodea: el albañil, el contratista, el arquitecto y el ingeniero. Estas personas, que tienen conocimiento y experiencia en su campo, son clave para erguir edificios culturalmente apropiados que sean sostenibles, asequibles y transformacionales.

Si la meta de una arquitectura de EMI es construir edificios que se adapten a las comunidades a las que sirven, entonces la mejor manera de lograr esto, es contando con la participación de la mayor cantidad de personas locales posible. En todo el mundo, ministerios están encontrando nuevas formas de involucrar a las personas de las comunidades a las que sirven, tal y como EMI ha visto con nuestro bien establecido programa de administración de obra en Uganda, y el reciente programa en Nicaragua; las oportunidades de trabajo pueden afectar directamente las necesidades físicas de una comunidad, establecer relaciones y desarrollar personas a través del discipulado.

Entonces, una arquitectura de EMI debe trabajar con profesionales del diseño que sean locales; ellos son increíblemente valiosos porque pueden responder a un sinfín de preguntas como solo un local podría hacerlo, incluso si no saben la respuesta, sabrían dónde encontrarla; trabajamos globalmente pero pensamos localmente. Los proyectos diseñados por EMI para YUGO Ministries en México son un claro ejemplo de esto. Cada año YUGO recibe en sus centros de alcance a miles de misioneros de corto plazo, mayormente de América del Norte y México. Se diseñaron nuevas instalaciones para cada centro, con dormitorios, oficinas, áreas de reunión y adoración, así como espacios para el alcance de la comunidad. Los sistemas de construcción implementados incluyen cimientos de concreto armado, muros de carga a base de mampostería confinada y estructura de madera para muros interiores, y en los entrepisos un sistema local a base de viguetas de concreto y casetones de poliestireno. Los edificios fueron diseñados para integrarse al aspecto de la arquitectura local, combinando colores, materiales y formas tradicionales.

Sería fácil pensar que este es un ejemplo de una arquitectura de EMI; sin embargo, lo que fue único en este proyecto y en otros que EMI ha realizado, no fue el método de construcción ni los materiales utilizados, sino la forma en que se llevó a cabo el diseño. Tanto EMI (en diseño) como YUGO (en construcción) involucraron arquitectos e ingenieros locales desde el principio, con el objetivo de no construir sólo edificios, sino de construir personas. El proyecto permitió establecer relaciones, así como un sentido de comunidad entre los voluntarios, profesionales del diseño, contratistas y mano de obra local; la base de este equipo interdisciplinario e intercultural fue la colaboración: trabajar juntos, escucharse unos a otros y aprender juntos. "Hacia una Arquitectura de EMI" va más allá de nuestros diseños, nuestros dibujos y nuestros detalles.

The EMI Fund

The EMI Fund supports all that we do at EMI. With a strong foundation, we can keep designing a world of hope.

EMI Tech is looking for contributors – write to editor@emiworld.org with your topic and article outline.